Kenna Apartments: Early Modern Architecture in South Shore

Tucked away on a dense block of apartment buildings on 69th Street between Paxton and Crandon, the Kenna Apartment building at 2214 E. 69th Street doesn’t immediately call attention to itself. Like many neighboring buildings, it’s three stories tall, made of brick, with a hexagonal bay of windows projecting towards the sidewalk.

But look a little closer and you’ll begin to see that it’s special: the front door is flanked by elaborate stone carvings of a man, woman, and child; the wooden window frames bear intricate carved designs; and the brick corners of the protruding bay are delicately interlocking. Although subtle, these design details hint at the building’s distinguished architectural pedigree. It is the work of Barry Byrne, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright and one of the country’s most significant Prairie Style architects. The Kenna Apartment building is one of South Shore’s many gems, and quietly tells a story of how this neighborhood has nurtured some of Chicago’s best architecture.

John Francis Kenna

John Francis Kenna was an accountant living on the Near South Side with his wife and elderly father in 1915 when he decided to commission a new home and investment property for his family on an empty block of 69th Street. Kenna was part of an influx of Irish families moving to South Shore at the time, and the building was part of a neighborhood construction boom.

Although the block was empty when it was constructed, by the early 1920s the street would fill in with a solid wall of apartment buildings. Kenna and the rest of his generation transformed South Shore from an archipelago of sleepy hamlets lined up along the Illinois Central railroad’s South Chicago branch into a vibrant neighborhood densely populated with upwardly-mobile families. These early investors dreamed and built big, lining the streets with new buildings in the best styles of the day – from traditional Neo-Gothic mansions, classic bungalows, exotic Spanish revivals, and the cutting-edge fashion of the time: Prairie Style.

Barry Byrne, Architect

To design his building, Kenna chose promising local architect Barry Byrne. Raised on the West Side of Chicago, Byrne’s architectural career began in 1902 when he was 19 years old. Having seen a picture of a building by Frank Lloyd Wright in a magazine, he marched into Wright’s studio – without any experience, or even a high school education – and talked his way into a job. As luck would have it, the young Byrne got to be involved in the design of some of Wright’s most famous buildings, including Oak Park’s Unity Temple (1905-08).

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1905-08. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

In the fast-paced and free-spirited atmosphere of the studio Byrne quickly absorbed the fundamental lessons of Wright’s famous Prairie Style, including open floor plans, natural materials, and organic decoration.

Although working closely with Wright had its benefits, the studio was chaotic. A few years into Byrne’s time there, Wright began an illicit affair with the wife of one of his clients, and was increasingly absent from the office. Tired of picking up Wright’s slack, Byrne quit his job, and worked briefly with another defector from Wright’s studio, Walter Burley Griffin.

Walter Burley Griffin’s Gauler Twin Houses, 5921 & 5917 North Magnolia Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 1908. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

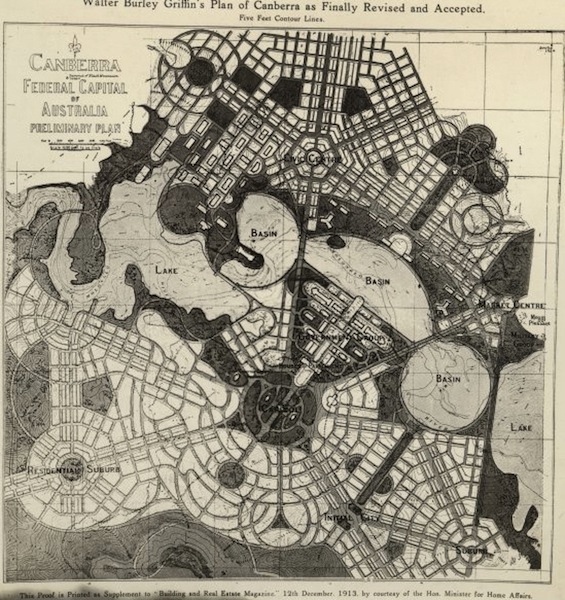

Byrne lived on the West Coast from 1908 until 1914, when he returned to Chicago to keep Griffin’s studio running while Griffin went to Australia to design that country’s new capital city, Canberra. The arrangement between Byrne and Griffin only lasted until 1916, when the two architects fell out over Byrne’s re-designing of some of Griffin’s projects.

Walter Burley Griffin’s plan for Canberra, Australia, 1913. Source: Wikipedia

The years leading up to 1916 were formative for Byrne, as he began to turn the lessons he learned in Wright’s studio into his own unique style – one characterized by clean minimalist lines and meticulous attention to detailing.

University of New Mexico Chemistry Building, project initiated by Walter Burley Griffin and design executed by Barry Byrne, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1915-1916. Source: University of New Mexico Heritage Preservation Plan, 2006, photo by Cynthia Martin.

It was also during these years that Byrne was introduced to sculptor Alfonso Iannelli, with whom he would collaborate on several projects, including the Kenna Apartments.

Sideways Apartments

Kenna’s commission came at a crucial point in Byrne’s career. He had left behind Wright, Griffin, and the other architects with whom he’d partnered early on, and was finally setting out all on his own. The apartment building was an opportunity to make a reputation for himself. Kenna was an ideal client – “architecturally unselfconscious,” and willing to let Byrne do pretty much whatever he wanted with the design. Kenna’s building permit was issued and work began in the spring of 1916.

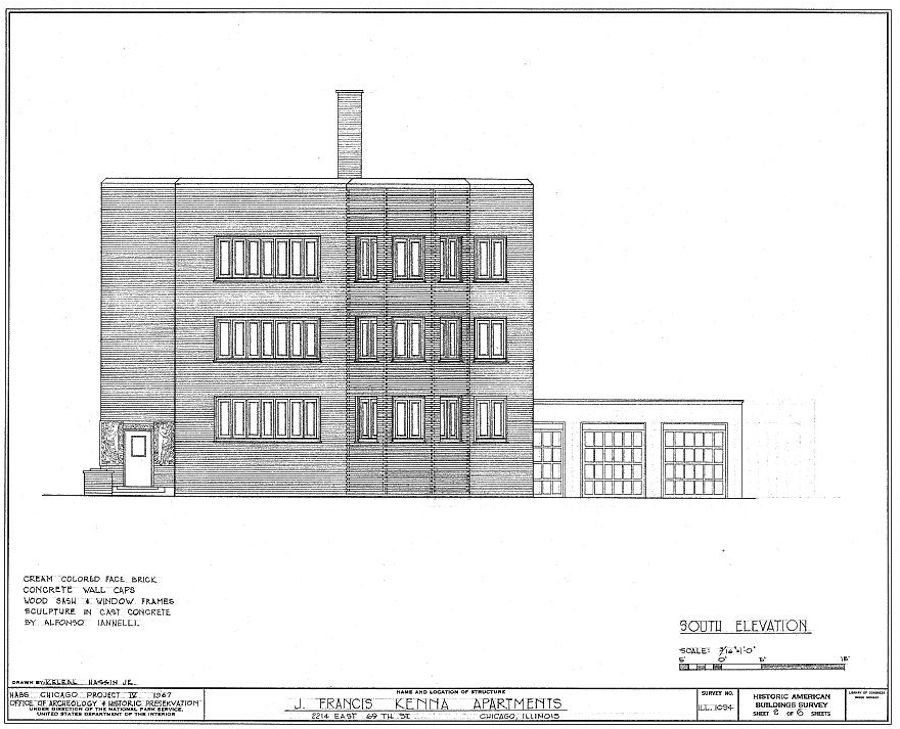

South Elevation of Kenna Apartments. Source: Historic American Buildings Survey

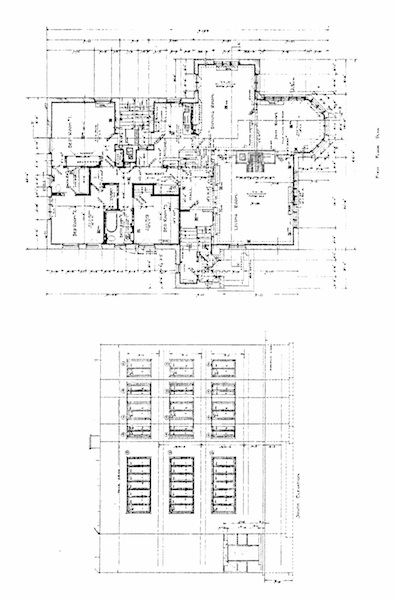

Byrne took advantage of this freedom and Kenna’s wide lot, delivering a radical re-conceptualization of a traditional building type. The apartments are laid out like traditional 3-flat plans rotated ninety degrees – the public spaces of the living room, dining room, and sunroom are all lined up along the front of the building in order to take advantage of generous rows of windows facing south.

Plan of Kenna Apartments, by Barry Byrne. Source: Chicago Landmark Designation Report

“Brick Architecture in its Purest Form”

The building’s exterior is similarly radical in its austerity. Like his mentor Wright, Byrne believed in architecture that celebrated simple materials, and he applied decoration judiciously. The humble brick is the most common material for Chicago apartment buildings, and so Byrne built for Kenna an example of “brick architecture in its purest form” (according to the City of Chicago Landmarks Designation Report). In a 1930 essay on “Distinction in Brick Architecture” Byrne described his approach to building materials:

Materials for building purposes, whether they are the most precious, or the simplest, have their own character and beauty. As a matter of fact, the beauty of material is secondary to the beauty of the way in which it is used.

True to this philosophy, the Kenna Apartment’s walls are smooth and monumental planes of yellow brick, interrupted only by marching rows of windows. Attention is called to the individual bricks that make up these walls through the use of deep joints between them, and at the protruding bay on the front of the building where corners are formed by the brick ends locked together like fingers in clasped hands.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

The Kenna’s plain brick walls may not seem like such a remarkable architectural statement, until you consider the alternatives. In 1916, apartment buildings in Chicago were typically built with stone or terra cotta trim and extremely thin joints between bricks in order to mimic the appearance of more dignified carved stone architecture.

It would be many years before the minimalist modernist aesthetic of architects like Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Adolf Loos, in which simple materials were left unadorned and celebrated for their inherent characteristics, would receive widespread popularity.

Adolf Loos’ Tristan Tzara House, Paris, France, 1926. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

In 1916 (a full decade before the avant-garde Adolf Loos house pictured here), the Kenna was a daring and unusual argument for the use of restraint and simplicity in architecture for the middle class. We’re all living in these piles of bricks, Byrne might have noted, so why not celebrate the brick instead of hiding it?

Adolf Loos’ Tristan Tzara House, Paris, France, 1926. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Sculpture: “The Flower of Architecture”

Of course, the Kenna is not totally devoid of decoration, but these elements are confined to a few key spots where they will have the most power.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

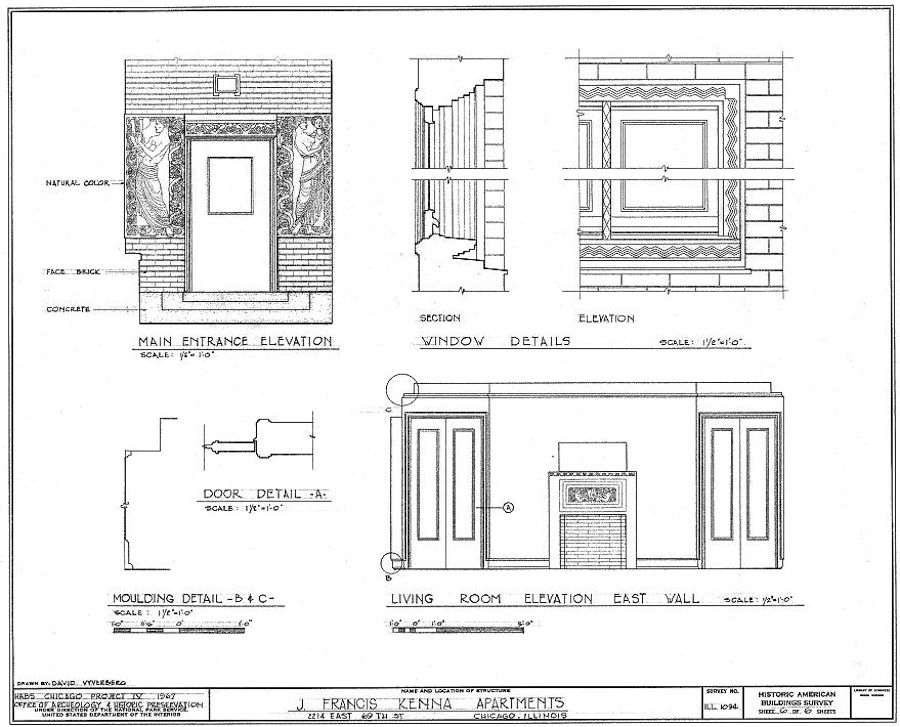

The window frames, not usually a site of decoration, are carved into an unusual zig-zag profile, providing a delightful detail that draws attention to one of the building’s most important interior features: abundant windows and natural light.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Byrne also tapped his sculptor friend Alfonso Iannelli to design concrete panels to surround the door. Iannelli was a friend of Wright’s, and would go on to collaborate with Byrne on a number of buildings, including the famous St. Thomas the Apostle Church and School in Hyde Park.

St. Thomas the Apostle Church and School, by Barry Byrne with sculpture by Alfonso Iannelli. Hyde Park, Chicago, Illinois, 1929. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Iannelli and Byrne shared similar philosophies about the role of decorative sculpture in architecture. In a 1929 article, Iannelli writes:

Sculpture may be considered the flower of architecture, but it must be an organic part of the whole, as the flower is one with roots and stem. The movement of the sculpture should grow from the structure itself, being so much a part of the plan, that were the sculpture eliminated, the building would be incomplete, and if its movements were not those of the structure, it too would be a failure.

St. Thomas the Apostle Church and School, by Barry Byrne with sculpture by Alfonso Iannelli. Hyde Park, Chicago, Illinois, 1929. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

This philosophy is certainly borne out in the Kenna. In two small concrete panels on either side of the front door, Iannelli provides enough decoration to serve the entire building; the delicate curves in Iannelli’s compositions are a perfect counterpoint to the geometric severity of the architecture.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

The swooping, dancing figures greet visitors and residents as they enter the building, but the humble concrete out of which they are formed and the stony set of their faces prevents their presence from seeming overly sweet or cute.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Byrne and Iannelli’s decorative scheme is quiet, understated, and lyrically powerful.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Byrne was delighted with the building. Later in life he would identify it as a significant breakthrough in his career, and one that helped lead him towards his signature style of stripped-down modernism enlivened by custom sculptural embellishments.

Architectural Details of Kenna Apartments. Source: Historic American Buildings Survey

Mr. Kenna also loved his high-fashion building. He originally intended to charge $60 a month in rent for the first and second floor apartments (he lived with his wife and father on the third story), but found that he was able to double this figure to $120 due to Byrne’s sophisticated design – the equivalent of about $2,500 in 2013 dollars.

South Shore Neighbors

In the nearly 100 years since the Kenna Apartments were built, South Shore has changed and grown, but Byrne’s creation has remained a meaningful feature of the neighborhood. The building’s high-quality design continued to attract discerning tenants of means; in December of 1951 its address appears in a Chicago Tribune notice about a mink coat stolen from one of the apartments, which was worth $5,250 – approximately equivalent to $47,000 today.

Source: Chicago Tribune, via ProQuest

The natural and architectural beauty of South Shore – including landmarks like the Kenna Apartments – have always attracted and inspired creative types. If you were sitting on the front steps of 2214 East 69th Street around 1927, you might have seen a young boy skipping by, on his way from his home on Paxton at 67th Street to his job running errands for spare change. He might have stopped and stared at the Kenna Apartments for a little bit longer than other children, puzzling over its unusual appearance. That boy was Walter Netsch, who would grow up to become one of Chicago’s most important mid-century modern architects, and the person responsible for the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle Campus, among other notable works.

Decades after his first childhood encounter with the Kenna Apartments, Netsch would recall in his oral history the stunning impact that this one building had on his young mind. Of course at age 7 he knew nothing about architecture, modern or otherwise; he says “I only knew it as something different that I liked.” Its “clean” and “geometric” details stuck with Netsch for the rest of his life.

The echoes of Byrne’s simple materials and heavy massing can be seen in many of Netsch’s most famous works, including the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library and many of the monumental Brutalist buildings on the University of Illinois at Chicago campus.

Walter Netsch, Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago, 1970. Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

In August of 1990 Chicago’s Landmarks Commission recognized the significance of Byrne’s apartment building to the entire city’s architectural heritage, and named it a City of Chicago Landmark. This designation protects it from alteration or demolition so it can be appreciated by future generations of Chicagoans – although given that its original design pleased 75 years of owners and residents, a desire or need for alterations to Byrne’s masterful and innovative design seems unlikely.

Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns

Further Reading:

- Chicago Landmark Nomination for the Kenna Apartments

- The Architecture of Barry Byrne, by Vincent Michael

- WTTW Chicago Tonight: The Architecture of Barry Byrne

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) report and drawings

This was fantastic! I knew that Barry Byrne changed up the design of the church when he did St. Thomas the Apostle. (Hyde Park) This makes me want to learn more about the works of Francis Barry Byrne.

Thanks for this. Must admit Frank Lloyd Wright was a genius and his apprentices were equally as well.

Thanks Andi Marie! And it is amazing how such a small group of people were so influential. I think I want to focus on Walter Burley Griffin next…

Thank you, Eric and Susannah. Beautifully done, putting one of South Shore’s many architectural treasures in context

with Byrne’s predecessor and successors.

Thanks Mary! Can’t wait to show off more of the neighborhood, though we will be covering things elsewhere too.