Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Charnley House, Part 1

[Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

That, one, Wright was known to make misleading and self-serving statements during his entire career, which will be discussed throughout this article. Secondly, Sullivan’s geometric experimentation and specific design process were key components of the Charnley design, whereas Wright’s early output did not exhibit anything remotely close to Charnley’s ingenuity. If one is to believe Wright at least contributed certain elements to the Charnley House then the argument can also be made for another one of Sullivan’s employees at the time, Irving Gill. Furthermore, Sullivan’s relationship with the Charnleys themselves cannot be dismissed; their similar temperaments and closeness suggest Sullivan had some influence over its design. This was not just a residential commission for some random client. And finally, the home’s motifs, exterior, and manipulation of space are all trademarks of Sullivan’s work.

Although Wright might have considered himself a fully developed individualist at birth, it was Sullivan who truly shaped him. During his time working for Sullivan, the young and relatively inexperienced Wright blossomed into the modernist he’d be known as for the rest of his life. The Charnley House, whether a collaborative design or not, served as a model for Wright’s earliest work as an independent architect, specifically the Winslow House, built in 1894, which shares many similarities with Charnley. Even though the architects had a falling out when Sullivan fired Wright in 1893 (Wright once again bended the truth by claiming he quit), the men reunited near the end of Sullivan’s life. Wright sometimes downplayed Sullivan’s overall influence, but one cannot deny the importance Sullivan had on Wright’s design philosophy.

There would be no Wright without Sullivan.

Contents

- Intro

- Lieber Meister

- Sullivan’s Experimental Phase 1887-1890

- Wright’s Early Career

- Equisse

- Irving Gill

![Louis Sullivan in 1890, the year before he designed the Charnley House, and Frank Lloyd Wright in 1887, shortly after he arrived in Chicago. Wright worked for Adler & Sullivan between 1888-1893. [Ryerson and Burnham Libraries/“Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography” by Meryle Secrest]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/PhotoGrid_1475298229160-900x900.jpg)

Louis Sullivan in 1890, the year before he designed the Charnley House, and Frank Lloyd Wright in 1887, shortly after he arrived in Chicago. He worked for Adler & Sullivan between 1888-1893. [Ryerson and Burnham Libraries/Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography]

Lieber Meister

A great deal has been written about the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright on modern architecture, but what exactly inspired the architect? Wright rarely acknowledged any direct influences, because after all he was a creative genius at birth, right? But kidding aside, most architectural historians agree there were five critical factors in the shaping of his architectural philosophy: nature, music, the geometry of Froebel blocks, Japanese art and architecture, and the work of Louis Sullivan. Dismissive of others, even whose work he downright copied, like Joseph Olbrich’s Exhibit Hall (1897) in Vienna, Sullivan was the only architect Wright ever acknowledged during his lifetime. Wright referred to Sullivan as Lieber Meister (a German word meaning “Beloved Master”). One cannot disregard the importance of these influences on Wright; they were so necessary that if one was missing from the equation, his life might have turned out a bit differently. Would he still have become “the world’s most famous architect” if he had not been introduced to both Japanese art and Sullivan’s ideology? He wrote in An Autobiography that he could still feel the shapes of the smooth wooden maple Froebel blocks (the cube, sphere, and triangle) but what would have happened if he had also not been exposed to its geometry? Not every person who played with Froebel blocks as a child and studied nature and collected Japanese art prints and listened to music grew up to become an architect, let alone a great one, but the same cannot be said for the people who worked in Sullivan’s sphere.

![Froebel Blocks [ArchiTech Gallery]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/froebel.jpg)

Froebel Blocks [ArchiTech Gallery]

Sullivan’s Influence

Architecture is a collaborative process, where people draw ideas from the work of others, especially from the people in charge. Wright was not an exception to this rule. A number of architects who worked under Louis Sullivan, including Irving Gill, George Elmslie, Richard E. Schmidt, and Parker N. Berry, all went on to create avant-garde structures during their own independent careers. Like Wright, they created a new type of architecture completely or nearly free of historical precedent. Now venerated as the “father of modernism,” Sullivan was instrumental in the overall development of all these men (and women like Marion Mahony, Wright’s later assistant, who credited Sullivan as the main force behind Wright’s Prairie School style in her book The Magic of America). Although Sullivan’s impact on Wright has been dismissed by some in the past (and even to this day), this is simply not the case. Most likely historians, such as Lewis Mumford, took Wright at his word. In a letter from 1930, six years after Sullivan’s death, Wright wrote to Mumford “though pupil, I think I was never his disciple. Sullivan is on record as gratefully acknowledging this.” Wright’s declaration contradicts the actual evidence. Just like the others who worked under Sullivan, Wright was a disciple. As Wright moved away from his first employer Joseph Silsbee’s historic-influenced Shingle Style, he refined Sullivan’s philosophy as his own, creating a purely American form of architecture, later known as Prairie Style.

The Montgomery Ward Company Complex, designed by one of Sullivan’s disciples, Richard E. Schmidt, in 1907 was a pioneering structure in its use of reinforced concrete. Sullivan’s influence is found in the strong geometric forms and rich terra-cotta ornament. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Sullivan’s Experimental Phase 1887-1890

![View of H.H. Richardson’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1887) in 1910. [Historic Architecture and Landscape Image Collection]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Screenshot-2016-09-13-at-11.49.21-PM.png)

H.H. Richardson’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1887) in 1910, 25 years after its construction. [Historic Architecture and Landscape Image Collection]

Before the Charnley House, Louis Sullivan had been experimenting with the geometric simplification of surface and mass for a three-year period between 1887-1890, which was sparked by the design for Chicago’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1885-87). Considered one of the most important commercial structures of the nineteenth century, Sullivan described it as “massive, dignified, simple…a monument to trade.” The building’s architect, H.H. Richardson, had a huge impact on Sullivan, who began creating his own interpretations of Richardson’s work, borrowing the basic geometric clarity of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture but taking it to a whole new level. Sullivan’s now demolished Walker Warehouse (1888) and Auditorium Building (1889) both clearly reference Richardson’s Wholesale Store.

![Adler & Sullivan’s Walker Warehouse (1888) not long before its demolition in 1953. [Richard Nickel Archive]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Screenshot-2016-09-13-at-11.57.24-PM.png)

Adler & Sullivan’s Walker Warehouse (1888) not long before its demolition in 1953. [Richard Nickel Archive]

![Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building (1887-89) under construction in 1888. [Sullivaniana Collection]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Screenshot-2016-09-14-at-12.14.38-AM.png)

Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building (1887-89) under construction in 1888. [Sullivaniana Collection]

Walker’s design was especially noteworthy in its display of total abstraction. Wright wrote in Genius and the Mobocracy, an intimate account of his personal and aesthetic relationship with Sullivan, that the architect said the building was “the last word in Romanesque” with its smooth ashlar masonry and exclusion of heavy texture around the arches. The Auditorium Building, where Sullivan moved his architectural firm into the top floor of the tower, originally had a different design in the works. But after seeing the Wholesale Store, Sullivan instead simplified the building’s elements to mass, texture, and proportions.

Martin Ryerson Tomb (1887) in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Although Sullivan was known for his highly personal ornament, which first made an appearance in the interiors of the Auditorium Building, Sullivan questioned its overall use in “Ornament in Architecture” in 1892:

“I take it as self-evident that a building, quite devoid of ornament, may convey a noble and dignified sentiment by virtue of mass and proportion…I should say that it would be greatly for our aesthetic good if we should refrain entirely from the use of ornament for a period of years, in order that our thought might concentrate acutely upon the production of buildings well formed and comely in the nude…”

Written the year after Charnley was conceived, Sullivan’s words were a reflection of his work during 1887-1890 when he incorporated elements of Richardson’s work and created something original. In order to produce a completely new form of architecture, he had to eliminate most decorative elements and focus only on surface and mass. He eventually began to overlay his buildings with ornament, but time and time again he would return to his experimental stage, as seen in later buildings like Harold C. Bradley House (1909) in Madison, Wisconsin and the Van Allen Building (1913) in Clinton, Iowa. Even the facade Sullivan designed for the Gage Group Buildings in 1898 is understated, although still expressive, with its emphasis on the structure itself.

Sullivan’s design for the Gage Group Buildings facade in 1898. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Wright’s Early Career

Marie Schock House in Chicago’s Austin, built in 1888. [Photographer: Bob Thall]

Frank Lloyd Wright’s own home in Oak Park was located just two miles from Chicago’s Austin neighborhood where Frederick Schock designed an inventive Shingle-Style house for his mother. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

One of Wright’s “Bootleg Houses,” the Robert Parker House in Oak Park, shows the significance of Silsbee on Wright in the 1890s. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Streetview of the Nathan Moore House in Oak Park, soon after its completion in 1895. [Wright 1895-1916]

Garden view of the Nathan Moore House after it was rebuilt by Wright in 1923. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

![The shingled-styled George W. Smith House in Oak Park was designed four years after the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/4_bTKBffL-900x653.jpg)

The shingled-styled George W. Smith House (1895) in Oak Park was designed four years after the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Dr. Allison W. Harlan House (1892) in Chicago’s Kenwood was the only one of Wright’s “bootlegs” to show Sullivan’s influence. [Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]

The only known photograph of the shingle-styled W.S. MacHarg House (1892), located in Chicago’s Uptown area. [Ryerson & Burnham Archives]

James Charnley House in 1892. [Historic Architecture and Landscape Image Collection]

Equisse

The Charnley House is an excellent example of how the facade reflects the underlying plan or the function of the building. After all, the phrase “form follows function” has been famously attributed to Louis Sullivan. Sullivan always started with a plan first through equisse or the “initial sketch,” an idea Sullivan first learned at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris, which helped to shape the home’s overall design. Although Sullivan wasn’t a Beaux Arts architect in the traditional sense, he took this idea and practiced it for the rest of his career.

In The Autobiography of an Idea, written in 1924, Sullivan expounded on his philosophy in that “one hold to the original sketch in its essentials.” Instead of imitating historical styles, Sullivan attempted to create a new grammar of his own, not only through the concepts he learned at EBA (as well as at MIT) but also through the work of H.H. Richardson, which was discussed earlier. While people think of Beaux Arts as a style, which it is, it’s also important to remember it as a manner of training. Emphasis was not only placed on the superficial element of how it should appear but also its appropriateness and function; how the building works and what it should do. This explains why a number of Beaux Arts-trained architects had no problem jumping from style to style, whether it be Baroque or Neoclassical or Art Deco. The idea of expressing the functional character of a building is something Sullivan learned at EBA and applied to his organic architecture, which was then carried on by Wright. Sullivan would take an idea, which did not deviate too much from its original form, and hand it over to a draftsman, like Wright for example, who would translate Sullivan’s ideas but again would adhere to the “initial sketch” as closely possible. Wright would exaggerate the truth by turning this process of “translating” into “inventing”. Wright would apply a similar method almost half a century later when designing his most famous building.

![Fallingwater, Wright's most famous work, not long after its completion in 1937 when the architect was 70 years old. [Hedrich Blessing]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Screen-shot-2016-10-03-at-9.24.35-PM.png)

Wright’s most famous work, Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, not long after its completion in 1937. [Hedrich Blessing]

Fallingwater

Although Wright had visited the site for Fallingwater several times during the previous year, he did not commit an actual design to paper, contradicting what he had written in letters to the client. When the client Edgar Kaufmann called one day from Milwaukee and said he was 140 miles away from Wright’s home at Taliesin, the architect enthusiastically said “Come along, E.J. We’re ready for you.” although there was not a thumbnail sketch, an elevation, plan, or even a single presentation drawing. After hanging up the phone, the nearly 70-year-old architect then sat down at a drafting table and proceeded to draw – non-stop – while apprentices continuously fed him sharpened pencils. The design was set to paper as quickly as he could draw. After Wright created a number of drawings in 90 minutes, he turned them over to two apprentices, Bob Mosher and Edgar Tafel, who took over from this initial design. Nothing was made out of thin air as Wright’s most famous work had lived as an “initial sketch” in his head for months before it was finally executed. This quick burst of creativity was a perfect example of what both Sullivan and Wright referred to as organic architecture. The differences between the design that day and the finished product are minimal at best. So how is this event any different than Sullivan’s practice of the “initial sketch”? Maybe the exact same thing happened during Charnley’s creation 45 years earlier? If architectural critics and historians consider Fallingwater to solely be a work of Wright’s, then can’t the same case be made for Sullivan and Charnley?

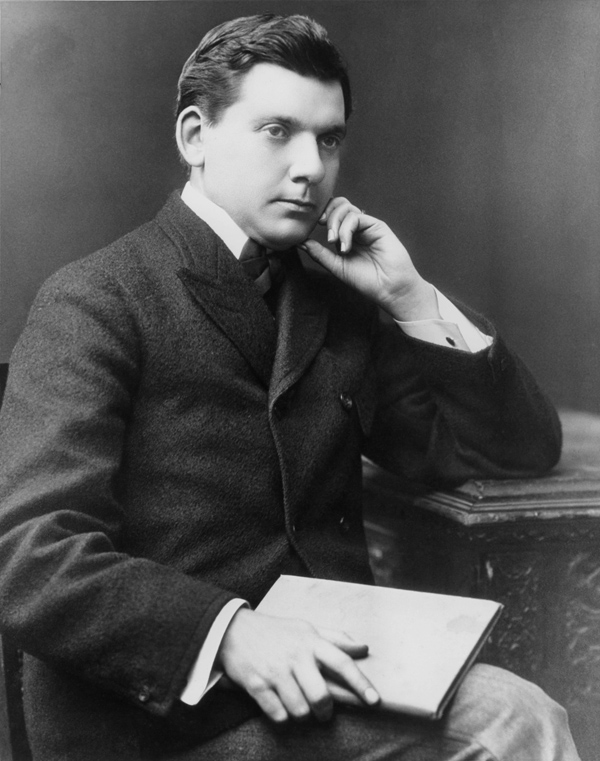

Architect Irving Gill, now recognized as a major figure in the modern movement, poses for a portrait in 1910. [San Diego History Center]

Irving Gill

Although dismissed by historian Tim Samuelson (who personally does not believe Gill contributed to Charnley’s design), one cannot discuss the Charnley House without examining the possible input of architect Irving Gill, whose work shared a number of similarities with Louis Sullivan. Before starting his independent career in Southern California, Gill had worked under Adler & Sullivan in Chicago from 1891-1893, specifically assisting on the plans for the Transportation Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition. He was also employed during the time of the Charnley design. Though not as well-known as Wright outside of architecture circles (he is celebrated by San Diego’s Save Our Heritage Organisation and Irving Gill Foundation) Gill was an important figure in the development of modern architecture. He was the direct connection between the Chicago School and Southern California’s modernist architects like Richard Neutra. Gill and Wright had similar career paths. Both worked for Joseph Lyman Silsbee before they moved to Sullivan’s office; Wright first in 1888, followed by Gill in 1891. Wright’s son Lloyd, who later worked for Gill, called him “the most original of all the architects (who had) stemmed from Sullivan and the Chicago group.” In typical Wright fashion, Frank responded to his son with a lie: “No. Gill worked for me at the office of Adler & Sullivan. Met Sullivan not at all. His work was inspired by the straight line and the flat plane of my own work and he liked to refer to himself as my disciple.”

These were rich words, considering Gill was directly involved with the Transportation Building, an important commission for Sullivan, who surely must have met him. Also, Gill and Wright were roughly the same age who followed the same exact path; both were students of Silsbee and Sullivan before starting their independent careers. And like Wright, Gill expounded upon the modernist principles he had first learned from Sullivan and practiced them throughout his career, specifically the idea that form should articulate function and buildings should be simplified into bold and expressive shapes. Wright was known for replicating Sullivan’s work, and Gill was no exception. The facade of Gill’s now-demolished Pickwick Theatre in San Diego paid homage to Sullivan’s Transportation Building and its famous “Golden Door” from the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

Sullivan’s Transportation Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition. [Ryerson & Burnham Archives]

![The facade of Irving Gill’s Pickwick Theatre (built 1904, demolished 1926) in San Diego paid homage to Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building and its famous “Golden Door” from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. [Ryerson & Burnham Archives/San Diego History Center]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/pickwick.jpg)

The facade of Gill’s Pickwick Theatre (built 1904, demolished 1926) in San Diego paid homage to Sullivan’s Transportation Building and its famous “Golden Door” from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. [San Diego History Center]

Allen House

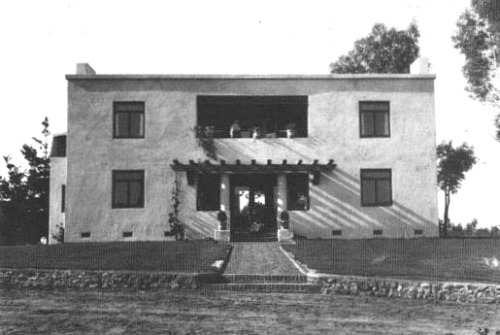

One cannot discuss the disputed authorship of the Charnley House without mentioning another example of Gill’s work that is reminiscent of Sullivan’s. The Russell C. Allen house (1907) in Bonita, California, may be the first intentionally anti-ornament structure ever built. Although architect Adolf Loos is usually credited with designing the first stripped-down, anti-ornament residence with the Steiner house (1910) in Vienna, Gill’s Allen house was designed three years earlier and deserves recognition. Gill had a brief but important partnership with Frank Mead; the Allen House is one of their collaborations.

As an apprentice for Sullivan at the time of the Charnley construction, one wonders how much of an impact Gill had on Charnley’s design (or how much Charnley influenced Gill)? On its own the Allen house is a remarkable landmark of early 20th century American architecture with its flat-roof, boxy shape, punched-in porches and windows, and cylinder columns.

Gill and Mead’s Allen House (1907) greatly resembles the Charnley House built 15 years earlier during the time Gill worked for Sullivan. [San Diego History Center]

[Ryerson & Burnham Archives]

References

- Hines, Thomas S. Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism: 1900-1970. New York: Rizzoli, 2010.

- Howard, Hugh. Architecture’s Odd Couple: Frank Lloyd Wright and Philip Johnson. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2016.

- Longstreth, Richard, ed. The Charnley House: Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Making of Chicago’s Gold Coast. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- O’Gorman, James F. Three American Architects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks and Peter Goessel, ed. Frank Lloyd Wright: Complete Works, Vol. 1, 1885-1916. Taschen, 2011.

- Twombly, Robert. Louis Sullivan: His Life & Work. University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Tremendous job!

And this is just part 1! Can’t wait to see the rest …

Excellent article. I enjoyed the words and photos very much. I am a Realtor in Evanston and took on this line of work because of a fascination with the Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and other classic architecture.

Noah Seidenberg

Well this really is really interesting indeed.Would love to study a little a lot more of this. Great publish. Many thanks for the heads-up. This weblog was really informative and kndoeewgabll.

Great work! I’ve also been looking into the claims by Wright and others on his work on Adler & Sullivan projects. In these cases Sullivan had a personal connection to the client. The Charnleys and Sullivan built vacation houses together in Mississippi before the Chicago house, MacHarg was a plumbing contractor on many A&S projects before the Berry-MacHarg House commission, Victor Falkenau was a builder on many A&S projects before the commission for his row houses. Plus there is the Albert Sullivan House, which was commissioned by Louis’s brother for their mother. Would an architect really turn these projects over to his assistant? Hope to see the next part of your article soon.

Incredible article. Of course I am a bigger fan of the Charnley House interior which clearly reflects Sulllivan in my opinion. Looking forward to part II !

A very thought provoking piece! From much recent reading of FLW history, I would guess that the truth is somewhere between your version and that of FLW. If you haven’t read it, the chapter ‘Liebe Meister’ in Meryle Secrest’s biography is very good on F’s early influences (ie copying). Scully cited a different provenance for the design of the Oak Park Studio – though yours is perhaps more convincing. What seems to be accepted is that LS did use FLW to produce house designs in the early 90s – if you have a Wainwright or Schiller scale project on your drawing board, a house would quite possibly seem a distraction, however well you might know the client. Didn’t FLW design a couple of houses for LS himself during that period? Looking forward to the next installment!

Definitely looking forward to future installments and further enlightenment presented in such a readable manner. In the absence of tangible documentation or other hard evidence, I submit that there can be no definite, final resolution of the question of “authorship.” The testimony of George Elmslie and Paul Mueller are the closest we have to contemporary evidence, and they point to FLW’s early and deep involvement in the house’s design. But the paucity of their statements creates questions of its own and does not permit a final resolution of the issue. In the end, I suspect we are left with an unsatisfactory inability to resolve the issue with certainty and we must instead satisfy ourselves informed and intelligent speculation regarding the contribution/collaboration of these masters. Freundt’s piece is a constructive and delightful addition to the literature. The focus of additional attention on this house is most appropriate. One is hard-pressed to think of many other houses that are the product of two masters of the craft. The handiwork of both Sullivan and FLW so fills this wonderful residence that, for that reason alone, the Charnley-Persky House is a treasure that brings a new delight and discovery with each visit. I excitedly await the next installment.

Regarding the W. S. MacHarg house…there is also a postcard view of Beacon Avenue, looking south which shows the house. Much like the known photo, a tree blocks the left (south) portion of the front facade, but the right (north) side of the house is partially visible, as is the incredibly steep roof, chimney, and at least 1 dormer window on the front of the house. The siding of the house appears much lighter than in the known photo, and had most likely been repainted.

My great grandfather was Allison Wright Harlan. My grandfather, the 6th child Marcus Aurelius Harlan, and his siblings lived in the house that Frank Lloyd Wright designed and built for them. I did not actually see the house, as it burned down in the 1960’s. My father John Allison Harlan told us about it, and how the boys would use a rope or sheets to climb down from the upper balconies.

Hi Laura. Thanks for sharing this. Do you (or anyone) reading this know the connection between Alison Harlan and Wright? It may have been thru the Unitarian Church that Wright’s uncle ran on the South Side. Or is the middle name Wright that somehow relates them?

The three-part façade and loggia of the Charnley house is very Renaissance Italian, which other than his time spent outside of Florence, is not something typically associated with Wright.

Hello Kevin. I live on Beacon and actually lived in the building that replaced the MacHarg home. I was curious if you could share the postcard view you mention or let me know where to look for it?

You can find the photograph on the Art Institute Site @ http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mqc/id/14482/rec/1

Thanks Michael! I am familiar with that photo. I had not seen the postcard view that Kevin refers to above and that was what I was referring to.

Please add links to parts 2 and 3. Thanks!

I am unofficially the local history and architecture expert for Beacon Street, and would also be very appreciative if someone could link to the postcard mentioned. Apparently Michael Plei is deceased, at an advanced age, and Dustin has moved abroad. Does anyone else know this postcard?

Hello Rachel,

I’m a few years late in replying, but only today (2023-09-29) did I receive this article (from architect friend, Frank Heitzman, in Oak Park). I appreciate your photo and reference to the Marie Schock House and your mentioning a strong theory that Frank Lloyd Wright was inspired by its west facade. My Partner, Bob Trezevant, is slowly working on trying to prove that theory (along with similar first-floor plans). I have the honor of owning that house (now 31 years); it was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1999 (along with three other Schock houses in the immediate area). It was a terrible mess when I purchased, but over the years I’ve made progress in bringing it back to life. And now I’m very pleased that it is included on a Chicago Architecture Center tour of the Austin neighborhood. Bob and I would be VERY pleased to discuss all this over wine!