The Wilbur and the 1879 “Philadelphia Plan” Street Renumbering

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

A few months ago columnist Gabriel X. Michael surveyed West Side houses with inscribed numbers that didn’t align with the current address. This was the result of the 1909 adoption of Edward Brennan’s plan which standardized addresses across Chicago.

Though this change affected most of the city, there was a large swath that escaped the 1909 change, including the house above.

A pre-1909 inscription on the entryway with an accurate address was quite curious.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

The Date and Address by the Door

While walking down Forrestville Avenue in Bronzeville, I noticed a man in front of a beautiful Rennaissance Revival house. I asked him how long he has lived there, and what he knew about its unique ornament.

Mr Edwards (above, pointing out address) noted the interesting exterior detailing, also pointing out that the build year and address was inscribed by the door.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

The build year was “AD 1894.”

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

The other detail was the address, 4329 [Forrestville].

Given the pre-1909 build year, I thought the address inscribed must be incorrect. But Mr. Edwards noted it was in fact correct. How could this be if the city renumbered its addresses in 1909?

December 2, 1879 Chicago Daily Tribune announcing the passing of the Philadelphia Plan ordinance

The South Division Exception as a Result of the “Philadelphia Plan”

The reason why this and much of the South Side got to keep their address was the result of the 1879 adoption of the Philadelphia Plan.

The plan called for house numbers on North/South streets to correspond with numbered streets (ex: 23rd Street). A house between 43rd and 44th Streets would have a number in between–4329 in the case of the Wilbur apartments.

This accommodation was explained in the 1909 renumbering plan [PDF]:

North-south streets south of Roosevelt Road (Twelfth street) and east of the Chicago river were not affected by this address change. An ordinance passed by the City Council on December 1, 1879 had renumbered the streets in this area. […]

When Chicago streets were renumbered in 1909 the new system was altered slightly to accommodate this earlier renumbering.

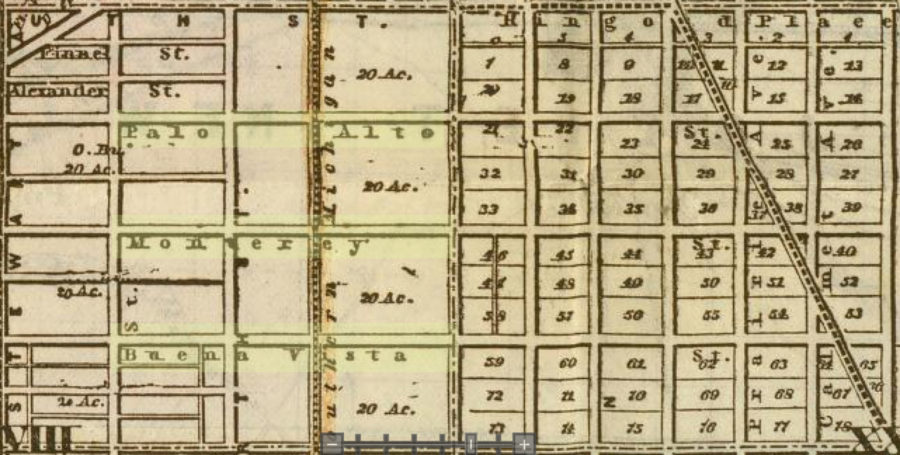

1862 Blanchard’s guide map of Chicago that predates the numbered street system. Courtesy of the David Rumsey collection

The Philadelphia Plan worked for the South Side (or South Division, as it was known then) because of numbered streets, which were put in to use around 1868.

In the 1862 map above, note the highlighted streets: Palo Alto, Monterey, and Buena Vista.

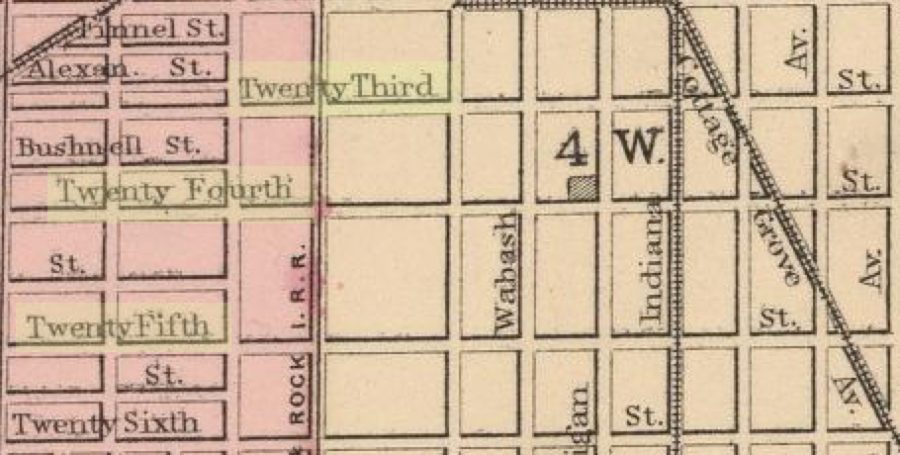

1868 Chicago color map after South Side streets became numbered. Courtesy of the David Rumsey collection

By 1868, these streets were known as 23rd, 24th, and 25th, respectively.

Noted cartographer and historian Dennis McClendon gave a brief overview of this change in a forum discussion on “Why no 10th Street?”

Streets on the South Side were renamed with numbers around 1868, and they began with 12th Street. The reason for that is still unclear, but it probably was that it was (more or less) twelve blocks south of the river, the north-south dividing line at the time. House numbers did not coincide with street numbers until 1879, when Chicago adopted the “Philadelphia plan” of matching block numbers for the area south of 12th Street.

If you’re interested in historic maps, I highly recommend visiting Mr. McClendon’s collection at Chicago In Maps, as well as David Rumsey’s collection.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

A Cache of Decorative Ornament

Above the doorway where Mr. Edwards lives at 4329 Forrestville is a vast collection of Classical design details: the egg and dart, finials, high-relief faces, torches, dentils, and many other symbols of antiquity. How many different elements can you identify?

Who Was Wilbur?

Many turn of the century Chicago apartment buildings have a name etched in stone or terra cotta over the entryway, sometimes referencing a child, friend, loved one, or someone else close to the developer or architect.

In the photo above, “WILBUR” is prominently displayed on a ribbon. But who was he?

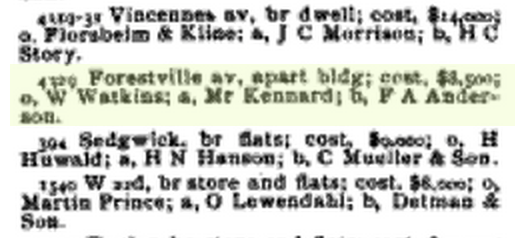

1874 Engineering Record showing address and build year

One clue is the building record from the February 17, 1894 edition of Engineering Record. It confirms the build date and address, which is incorrectly listed as 1891 by the Cook County Assessor.

Though a “W. Watkins” is listed in the record, it’s not “Wilbur.” It’s William Watkins, also found in an 1898 Chicago Blue Book of Selected Names.

If Wilbur was a real person connected to the developer or architect, the connection appears lost to history.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

Little Green Men

A more identifiable trait is the presence of two faces surrounded by leaves. If you’re a subscriber to the Neighborhood Notebook (our newsletter), you may recognize them. They’re known as the Green Man, and are frequently found in Romanesque and other styles influenced by the Roman Empire.

You can read more about them in the first issue of our newsletter.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

Like a Flowing Ribbon

The beautiful residence at 4329 Forrestville serves as a nice bookend to a long span of greystone row houses in the Romanesque style. The houses above are just south of it.

Forrestville Avenue is a great study on late 19th century architecture and the transitional era from Victorian splendor to a more restrained design a few years after the turn of the century.

John Morris/Chicago Patterns

The 1909 street renumbering led by Edward Brennan is one of the most important urban planning events for Chicago. Though not as ambitious, the 1879 adoption of the Philadelphia Plan was also an important milestone for normalizing the way we find places in the city.

Related Articles

References and Further Reading

- Rationalization of Streets (Encyclopedia of Chicago)

- Why No 10th Street? (South Loop message board)

- Chicago in Maps (Dennis McClendon)

- David Rumsey Collection – Chicago

- 1909 Street Renumbering (PDF)

Leave a Reply