Rachel Freundt

Rachel Freundt

July 26, 2018

[Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

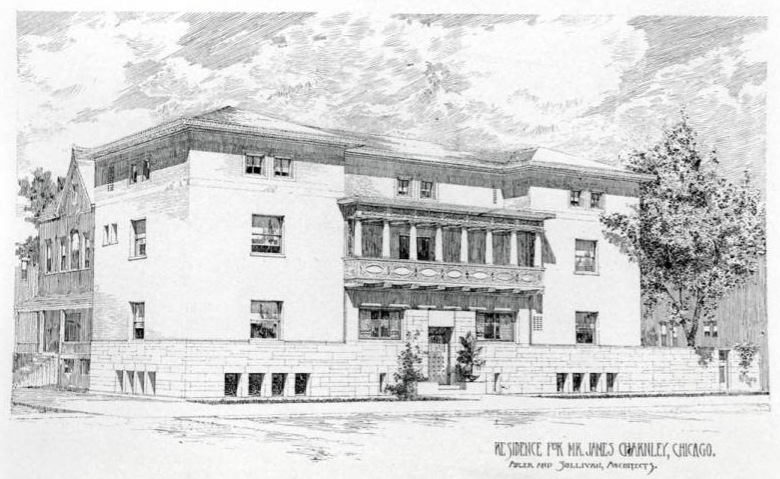

Although Evanston Alderman Anne Rainey called the Harley Clarke Mansion a “bundle of bricks,” the house is so much more than that. It is a National Historic Landmark, a part of the Northeast Evanston Historic District, and a lakefront jewel that perfectly symbolizes Evanston’s community, character, and history. It is also a piece of many people’s childhoods, mine included. Nearly thirty years ago, I attended art classes there when the mansion housed the

Evanston Arts Center. I’d like to think spending time in the Clarke Mansion is what influenced my love of architecture and old houses.

Now, the mansion faces demolition at the hands of a short-sighted Evanston City Council and a secretive, possibly self-serving group of nearby residents who want to see it obliterated. A tenacious group of local activists continue to organize to save it.

Continue reading »

Rachel Freundt

Rachel Freundt

March 28, 2017

A woman admires the “Fairies and Woodland Scenes” mural at George B. Armstrong School for International Studies in Chicago’s West Rogers Park. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

“Behind every great man there is a great woman” might just be the perfect expression to use for someone like

Marion Mahony Griffin. Although the second female graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) in 1894 and one of the first female licensed architects in the United States, Mahony Griffin was completely overshadowed by the men in her life. As Frank Lloyd Wright’s first employee in 1895, she worked as senior designer and lead draftsman until Wright closed down his Oak Park architectural studio in 1909.

Continue reading »