Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Charnley House, Part 2

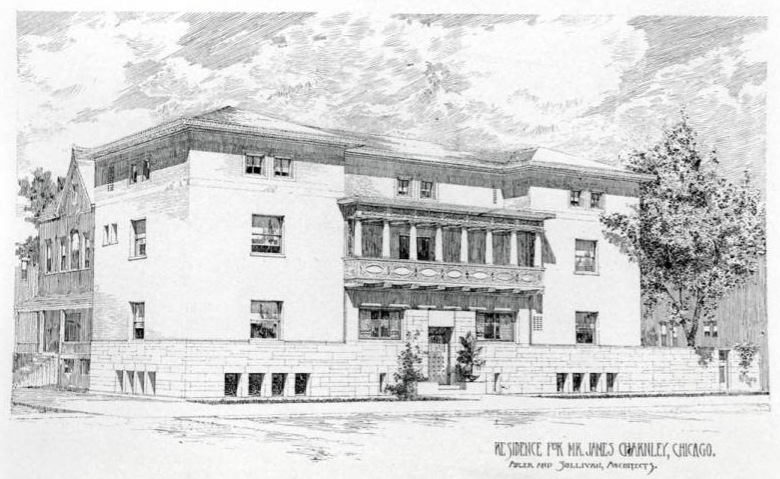

Architectural Drawing of the James Charnley House [Historic Architecture and Landscape Image Collection]

In Part 1 of “Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Charnley House” I discussed not only the controversy surrounding the home’s authorship but also both Sullivan and Wright’s architectural output during the years leading up to (and after) the home’s design. Between 1887-1890, Sullivan’s experimental period of creating buildings focused solely on surface and mass led to the development of his own personal style, while Wright’s work throughout the 1890s exhibited a number of features similar to his first employer Joseph Lyman Silsbee and historical revival designs. Although residential, Charnley fits in perfectly with the evolution of Sullivan’s architecture at the time. It was only after working for Sullivan that Wright’s architecture resembled the geometric clarity evident in Charnley, which will be discussed in Part 3 with an examination of the Winslow House. I also raised valid points in Part 1 related to Sullivan and Wright’s practice of organic architecture, specifically the initial sketch or “esquisse,” as well as the home’s possible connection to California modernist architect Irving Gill. This section will take a closer look at the misconceptions surrounding Sullivan’s residential designs as well as what exactly Wright worked on while employed for Adler & Sullivan, then explore the history and development of the Gold Coast neighborhood, followed by an examination of the Charnley family and their other residences before moving on to the house itself.

Contents

- Sullivan and Wright: Who Did What?

- History of the Gold Coast

- The Charnley Family

- The First Modern House in America

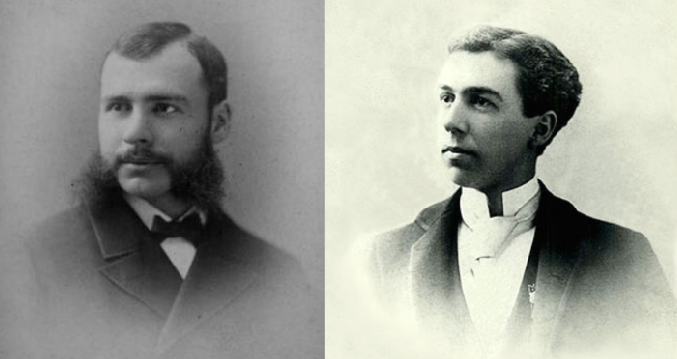

Portraits of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, both taken in 1886, two years before Wright started to work for Adler & Sullivan. [Ryerson and Burnham Libraries/Frank Lloyd Wright Trust]

Sullivan and Wright: Who Did What?

Before we look at the Charnley family and their famous house, let’s address one of the more popular misconceptions about Louis Sullivan. Besides Wright’s claims of solely designing Charnley in An Autobiography in 1932, Wright also declared in 1949’s Genius and the Mobocracy that “I designed the Charnley townhouse on Astor Street” because of the firm’s “refusal” to build residences. This statement was followed by 1954’s The Natural House in which Wright wrote “the firm [Adler & Sullivan] did not build residences,” especially after the Auditorium was erected in 1889. Is this true? Well, to a certain extent – but for anyone who has studied Wright, it is a well-known fact the architect continually made deceptive and self-serving statements throughout his 70-year career. Also, Wright’s rather inflated portrait of himself has been accepted as fact, instead of questioned, mainly because he lived long enough to “sell” his version of events.

During their partnership, Adler and Sullivan designed almost 200 buildings between 1880 and 1895. Before Wright joined the firm in 1888, nearly 60 residences, more than any other building type, were built. After the success of the Auditorium, the firm might not have forcefully sought out residential buildings but they did continue to design them (although the majority of them were unbuilt); 13 to be exact, or 2 a year. Not known to delegate responsibilities, Sullivan usually kept a close eye on his young staff, even when it came to residential work. Sullivan even continued to procure domestic commissions after he dissolved his business relationship with Adler, and a number of the designs, including the Henry Babson House (1907) in Riverside, Illinois and the Harold Bradley House (1909) in Madison, Wisconsin, continued the design principles first established at the Charnley House. I’ll go into more detail on those homes in the third part of the article.

Adler & Sullivan’s Joseph Deimel House (1885) at 3141 S. Calumet Avenue and Leon Mannheimer House (1884) at 2147 N. Cleveland Avenue in Chicago. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

A portrait of architect George Elmslie, circa 1912. [University of Minnesota Archives] The National Farmers’ Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota was designed by Sullivan and Elmslie in 1908. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

George Elmslie

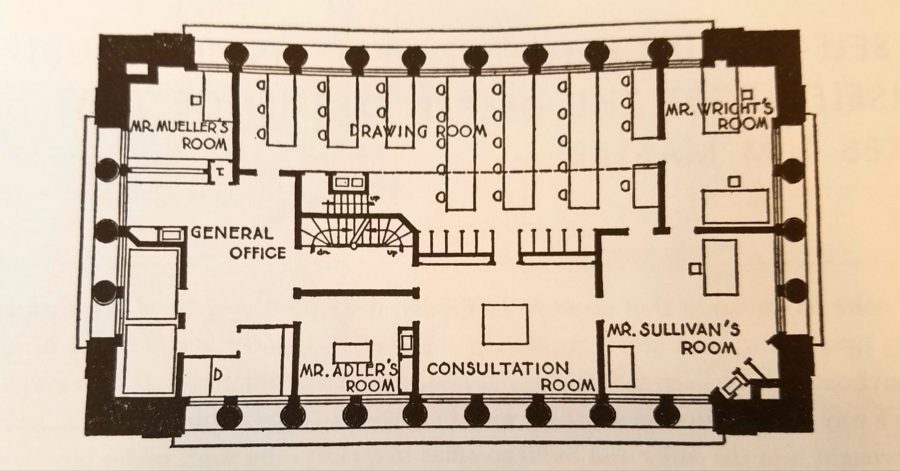

Sullivan and Wright’s working relationship cannot be discussed without mentioning another equally important player in Sullivan’s life, and that would be George Elmslie. Like Wright and Gill, Elmslie trained under Joseph Lyman Silsbee, before moving to the offices of Adler & Sullivan, supposedly on Wright’s recommendation. Two years younger than Wright, Elmslie was described in Wright’s An Autobiography as a “slow thinking, but refined Scottish lad who has never been young” while Elmslie’s architectural partner William Purcell said the exact opposite of Elmslie: “a man of quick imagination; his mind in architecture was highly articulate, succinct and competent.” Despite claims made by some historians and even by the architect himself, Wright was never chief draftsman in the Adler & Sullivan firm. Instead of having his own private office, Wright actually shared a small room with Elmslie.

Layout of Adler & Sullivan’s offices in the tower of the Auditorium Building. [Genius and the Mobocracy]

Unlike Wright, Elmslie did not declare every single Sullivan commission as his own. Elmslie even suggested Hugh Morrison’s 1935 monograph on Sullivan “attributes a bit too much” to him. While Elmslie had made a number of changes to the National Farmers’ Bank in Owatonna (Wright called it “one of [Sullivan’s] master works” as well as “a high wall with a hole in it”), he asserted other works, like the Bradley House, as “wholly Sullivan’s”. Elmslie was also quick to correct Wright, who had asserted the Schlesinger and Mayer Store (1899) as his own design, although he was no longer Sullivan’s employee during this period. Yet such a preposterous statement fits with Wright’s character, who at various times also claimed credit for Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium (the project was designed two years before he joined the firm), Wainwright Building, and Chicago Stock Exchange.

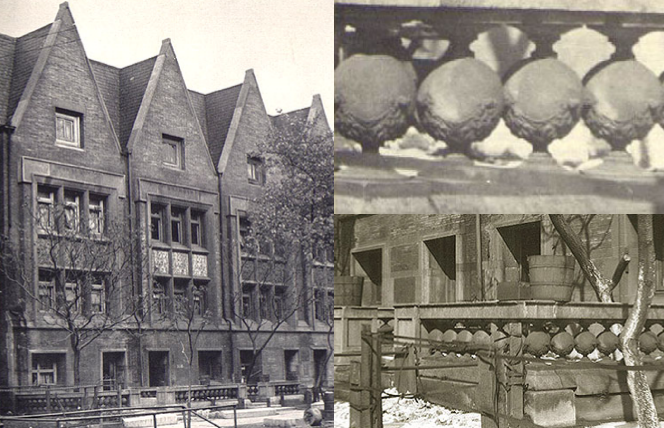

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robert W. Roloson Rowhouses in the 1930s with their original balusters, which were supposedly designed by George Elmslie. [steinerag.com]

Loeb Apartments (1891-92) and Victoria Hotel (1892-93) are Adler & Sullivan commissions but it is believed Wright had a hand in their designs. [Richard Nickel Archive]

Loeb Apartments and Victoria Hotel

While Frank Lloyd Wright asserted he solely designed some of Adler & Sullivan’s work in An Autobiography, George Elmslie recalled in the 1940s that Sullivan always saw drawings of works in progress, including the Charnley House.

“Yes he [Sullivan] did, knew all about it. Wright brought in his pencil 1/4 scales one morning and said ‘George this house is the result of my training here.’…Sullivan…of course followed the progress of affairs.”

As discussed in Part 1, the esquisse was important in Sullivan’s architecture and Elmslie confirms it with his statement. Wright would never have been left on his own as Sullivan was known to always supervise his draftsmen. But it is not difficult to see why an egocentric like Wright thought he was the one “inventing” these buildings rather than “interpreting” or “translating” the ideas coming from the chief architect and designer. Wright’s claims of “doing” a building – working on nights and weekends – is not the same as actually “creating” a building; it’s just well-established architectural verbage used when one prepares drawings. While Elmslie understood the difference between the two, Wright did not.

If Wright did not design Charnley House as he claimed, then what Adler & Sullivan buildings might he actually have contributed creatively? Backed up by Elmslie’s recollections of the structures as being “more Wright than Sullivan,” most historians believe Wright had more freedom in the creations of not the Charnley House, but the Loeb Apartments and the Victoria Hotel. Built at the same time as Charnley, the Loeb Apartments was located in an area full of manufacturing plants and storage facilities on what is now the northeast corner of Randolph and Elizabeth Streets on Chicago’s Near West Side. It was not a prominent commission, and that might have been the reason Sullivan gave his 24-year-old draftsman more leeway in its design. With the exception of Sullivanesque touches in the ornament in the window bays and arched entries, the stone and brick building is a rather unexceptional and somewhat awkward design. In 1957 Wright would even admit, although a bit reluctantly, to preservationist Richard Nickel that he designed the building. After Sullivan’s death, Wright was quick to claim Charnley but it took sixty-five years to acknowledge a less progressive design. Part of the building was demolished for the widening of Randolph Street in 1923, with the rest to follow in 1974.

In regards to the Victoria Hotel, Elmslie remembered Wright “worked on it a lot” with another draftsman at the firm, Louis Claude. The hotel certainly resembles Wright’s early work as an independent architect with its horizontal brick facade and hipped roof with overhanging eaves. Wright left the firm just as the building was nearing completion, and the next year in 1894 “copied” the Victoria Hotel’s use of projecting horizontal friezes of plaster ornamentation in Winslow House, which will be discussed in Part 3. Located in suburban Chicago Heights, the hotel and its storefronts were modified over the years and just before its scheduled demolition in 1961, the building was destroyed by fire.

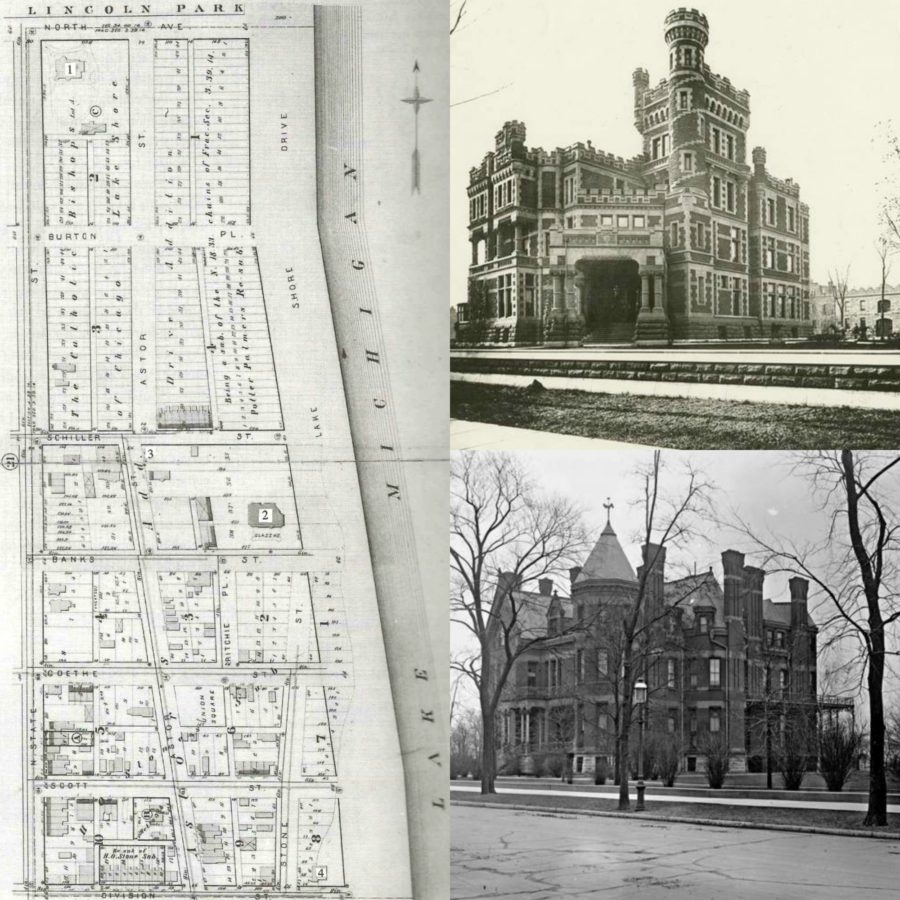

Robinson’s Atlas of the City of Chicago, Illinois in 1886: (1) Catholic Archbishop’s residence, (2) Potter Palmer’s “castle,” (3) future site of the Charnley house by Adler & Sullivan, (4) Charnley house by Burnham & Root. The residences of Potter Palmer and the Archbishop of Chicago are considered to be the first real homes of the Gold Coast. [Chicago History Museum/Chicago Tribune]

History of the Gold Coast

It is interesting to note that James and Helen Charnley were just as unique as their landmark home; not only were they pioneers in the development of modern architecture but also in the frog-infested swamp that we now call the Gold Coast. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the buildings located on the land owned by the Roman Catholic Church (the parcel went from Lake Michigan to State Street and Schiller Street to North Avenue) completely burned down and many North Siders fled to other parts of the city than rebuild. This tract of land was so empty (it was described by the Chicago Tribune in 1882 as “virgin ground…almost entirely free from objectionable buildings”) that a local toboggan club used it for outdoor activities. But in the 1880s developer Potter Palmer soon transformed the area with landfill, then convinced the city to build a seawall, just north of Bellevue Place, as well as create a relatively quiet boulevard, Lake Shore Drive, adjacent to his forty-two room mansion that was to be used for carriage rides up to Lincoln Park. Not only would these improvements enhance his property values but hopefully attract other affluent families to relocate here from Prairie Avenue and the South Side. An early resident, Louise de Koven Bowen, remembered Astor Street in 1890 as having “only three or four houses…that had just been redeemed from the beach…[and] digging the foundations of our house, workmen found numerous bones.” Yes, that’s right – the Gold Coast used to be a graveyard. The public Chicago City Cemetery was located in what is now the southern part of Lincoln Park, but the old Catholic Cemetery stretched along Astor Street until the 1860s. But that’s a whole other story! While Palmer’s “flagship mansion” was under construction from 1882-85, the Charnleys were the first wealthy family to actually move to the area that became the Gold Coast.

The Charnleys’ first home at Division and Lake Shore Drive, not long after its completion in 1882. Notice the “Palmer Castle” under construction in the background as well as the wooden pier over the marshy land that made up the Gold Coast at the time. [Chicago History Museum]

Edward G. Pauling Apartments (1886) at 1235-37 N. Astor St. [Richard Nickel Archive]

Passport photos of Douglas Charnley (1874-1927) in 1914 and his mother Helen Charnley (1856-1927?) in 1918, who both traveled through Europe after James Charnley’s death in 1905. [FamilySearch.org]

The Charnley Family

In examining the authorship of the Charnley House it is worth noting the close relationship that existed between Louis Sullivan and the Charnleys. This wasn’t just some unimportant commission. Even if Wright was correct in his declaration that “Sullivan did not design houses” after he joined the firm, the Charnley House was a very special case. While most of Adler and Sullivan’s business came through Adler’s connections, especially within the Jewish community on Chicago’s South Side, the Charnleys were personal friends of Sullivan, probably first meeting through their association with the Illinois Central Railroad. Sullivan’s brother Albert was an executive, later becoming general superintendent by the late 1880s, while Helen Charnley’s father served as the fifth (and later the eighth) President of the company. Known for its aggressive real estate development, in which it promoted communities as winter resorts for Midwesterners, especially along the Gulf of Mexico, Illinois Central was the connection that led the Charnleys and Sullivan to work together, not once but twice.

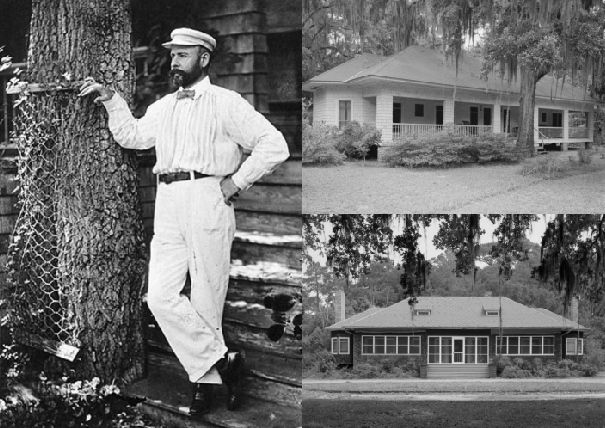

This portrait of Louis Sullivan at his cottage in Ocean Springs, Mississippi was probably taken in 1899 when he was 43 years old and working on his own without Dankmar Adler. [Ryerson and Burnham Libraries] Sullivan Cottage at top, Charnley Cottage on bottom. [Richard Nickel Archive]

Ocean Springs

The year before their Chicago residence was constructed, the Charnleys were on the train traveling down to New Orleans when they had a chance encounter with Sullivan, who was already an acquaintance. Sullivan was exhausted after the work that went into the landmark Auditorium Building. He had “rested up” in California before making his way to the Gulf Coast. It was during this trip that they decided to live next to each other. Both the Charnleys and Sullivan immediately fell in love with the Mississippi Sound; the couple purchased a twenty-one acre tract of land in Ocean Springs, Mississippi then sold five acres to Louis Sullivan for the sum of $1, with an understanding that he would design cottage bungalows for each of them as a winter getaway. The Charnleys, like Sullivan, were private people who rarely socialized so this arrangement was more than just convenient. It speaks to what must have been a close friendship (Sullivan and Mrs. Charnley were the exact same age) for they’d be sharing space in a remote yet natural setting. Unlike the other members of Chicago’s elite, the Charnleys did not live too extravagantly nor were they too concerned with impressing others; they chose an isolated, sleepy town of oyster shell roads and wild woods in Mississippi as their home away from home, far away from the fashionable resorts of the well-to-do on the East Coast and even nearby Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, then known as the “Newport of the West.”

Wright would also claim (later to be rejected by most scholars) to be the architect of these vacation cottages, which is hard to believe, especially when one of the homes was to be used by Louis Sullivan himself. Wright never even visited the site, a beautifully natural setting of oak, hickory, and pine trees that served as inspiration for Sullivan. In Autobiography of An Idea, Sullivan wrote that after designing the “two shacks” in March of 1890 the prepared plans were given to a local carpenter to construct. Sullivan personally landscaped the grounds to include two rose gardens, arranged in concentric circles. Photos of the house were published in Architectural Record in 1905, accompanied by an essay not by Frank Lloyd Wright but by Lyndon P. Smith, Sullivan’s associate on the Bayard Building in New York (1899). Sullivan lived here for the next eighteen years, staying for months at a time as his career slowed down. Unfortunately Sullivan’s beloved cottage was completely destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, but the Charnleys’ home has been rebuilt and is now open to the public.

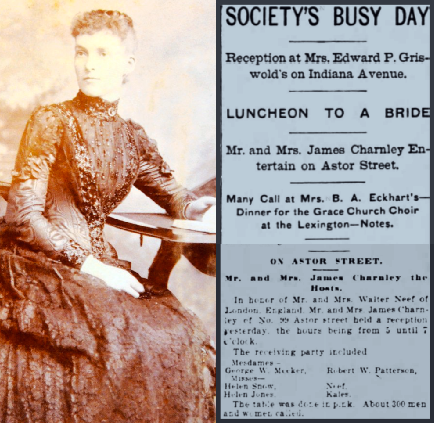

Portrait of Helen Charnley as a young woman, probably taken in the 1870s. Newspaper blurb about a social function at the Charnley home in February 1896. [Charnley-Persky House Museum Foundation/Chicago Inter Ocean]

On An Elder’s Trail

Although listed in the Chicago Blue Book, James Charnley, a partner in the prosperous Bradner, Charnley, and Company, was not your typical wealthy gentleman. There is evidence that shows the lumber merchant belonged to the Chicago Literary Club, but he was not associated with any other clubs nor anything related to the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, very unusual as it was Chicago’s most important social event at the time. Not a single photograph has been found of him. It is also worth noting that Helen Charnley, like her husband, was not as socially active as other ladies of the day and it is believed she did not belong to a single social organization. Yet their reputation for being extremely private is somewhat contradictory. In 1899 the Chicago Tribune listed her as a participant in a Christmas charity dance. The Chicago Inter Ocean, a newspaper published from 1872 to 1914, had a society article in which 300 guests attended a reception at the Charnley home in 1896. It was not until recently that a few photos of Mrs. Charnley were found – one dating from before the house was built and another taken long after she moved away from Chicago.

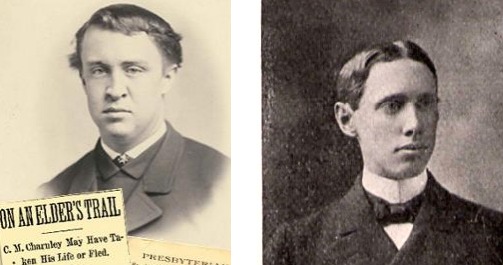

Portraits of Charles M. Charnley Sr. and his son Charles M. Charnley Jr. [Newberry Library/Yale University]

[Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The First Modern House in America

Long after the Charnley House was built, Frank Lloyd Wright proclaimed it to be the first modern house in America. No other house in the United States was like Charnley in its total abstraction, its scarcity of ornament (limited to specific areas in the balcony, cornice, and window grilles), and its manipulation of composition and scale. Built to the edges of a shallow 25 ft deep lot, the Charnley House appears to be a freestanding mansion with three finished exterior facades and one wall left blank in anticipation of an attached neighbor to the back. James Charnley had sold the adjacent lot directly to the east before he ever commissioned Adler and Sullivan to design the house; therefore the architects had to erect a party wall, and the only possible solution to bring extra light into a home with no back windows was to create a 30 ft high light atrium in the middle of the building. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Before the discussion of the home’s amazing interior, which will be discussed in Part 3, its equally unconventional facade must be thoroughly examined.

The Charnley House, just one and a half rooms deep, was built with a party wall because a home was supposed to be attached to the back of it. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Sullivan’s Schlesinger & Mayer Building exhibits his philosophy of the ideal tripartite skyscraper with a ground level base, followed by a number of stories designed to look all the same because they serve the same function, then topped with a distinct cornice line. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

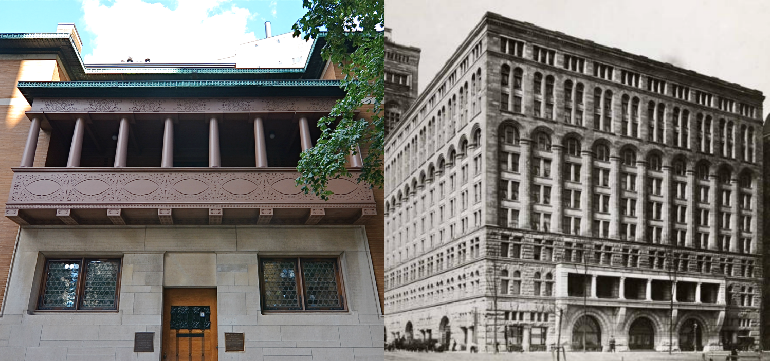

The open second floor loggias of Adler & Sullivan’s Charnley House and the Auditorium Building. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns] [Ryerson & Burnham Archives]

The limestone base of the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Design Motifs

Some historians, while questioning Frank Lloyd Wright as the sole architect of the Charnley House, believe he at least had a hand in some of the ornamentation. The design motifs, specifically the use of the pointed oval, circle-in-a-square, beading and dentil trim, are characteristic of both of Sullivan and Wright’s architectural philosophies at the time. It could be argued that the ornamentation, found on both the exterior and interior of the home, could possibly be a collaboration between the two architects.

Louis Sullivan’s Getty Tomb in Graceland Cemetery. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The oval motif is even found on the bottom of the home’s balcony. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

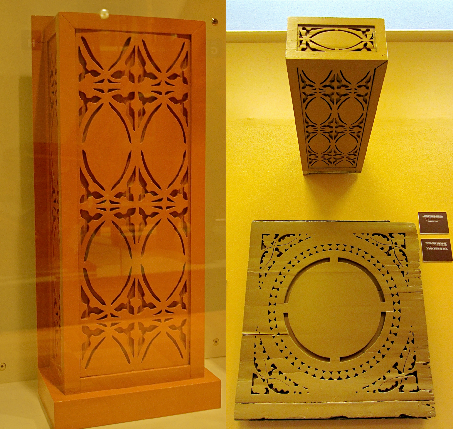

The original wood panels of the balcony, which was reconstructed by John Vinci in 1979, on display in the Met’s American Wing and the 2012 exhibit “Wright’s Roots” at Expo 72 gallery. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Examples of the circle-in-a-square motif include the balcony doors, fireplace mosaic, closet doors, and window grilles. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Close-up of the dentil trim underneath the staircase and the bead detailing. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

References

- Drury, John. Old Chicago Houses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1941.

- Gebhard, David. “Louis Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 19, No. 2 (1960): 62-68.

- Longstreth, Richard, ed. The Charnley House: Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Making of Chicago’s Gold Coast. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Menocal, Narciso G. Architecture as Nature: The Transcendentalist Idea of Louis Sullivan. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

- Nickel, Richard and Aaron Siskind et al. The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Osźuścik, Philippe. “Louis Sullivan’s Ocean Springs Cottages: A Vernacular Perspective.” Material Culture Vol. 41, No. 2 (2009): 38-56.

- Wright, Frank Lloyd. Genius and the Mobocracy. New York City: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1949.

Leave a Reply