Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Charnley House, Part 3

[Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The Charnley House, whether a collaborative design or not, served as a model for Wright’s earliest work as an independent architect, specifically the Willam Winslow House, built in 1894, which shares many similarities with Charnley. Besides Winslow, I will also discuss Sullivan’s later residential designs, specifically the Harold C. Bradley House in Madison, Wisconsin and the now-demolished Henry B. Babson House in suburban Riverside. Domestic architecture played a significant role in Adler & Sullivan’s practice in the 1880s. Although some historians dismiss Sullivan as a residential architect, these homes, designed near the end of his career, are just as interesting and important as any of his other commissions.

As mentioned in Part 1, the architects had a falling out when Sullivan fired Wright in 1893 for breaking his contract (Wright once again bended the truth by claiming he quit), but eventually repaired their relationship. As they communicated by letter and met in person, there are strikingly similar parallels during the teens and twenties as both men had difficulty securing commissions and struggled financially. Two important modernist architects, Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, knew Wright and Sullivan during this time period. Their recollections provide an intimate look into the lives of the mentor and apprentice as they experienced personal and financial struggles. In the series’ conclusion, I will discuss my own opinion related to the question of this series: Who designed the Charnley House? As someone who has spent close to a decade working inside the building, I probably know it better than most.

Contents

- An Unconventional Interior

- Winslow House

- A Closer Look at Babson and Bradley Houses

- The Final Days

- Conclusion

The entrance hall with mosaic fireplace inside the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

An Unconventional Interior

The Charnley House is a perfect example of how architecture must be experienced firsthand. As I already mentioned in Part 2, the interior is a one-of-a-kind space; not only was the home ahead of its with time an open floor plan but its emphasis on the vertical with a 30-ft high atrium was also atypical. For such an unconventional interior, the home’s rooms were not recorded as no plans or period photographs are known to exist. Many wealthy families at that time were known to document their personal residences and furnishings so this is quite unusual, especially when you consider the fact Adler & Sullivan chose to publish the design in a number of popular architectural journals. The house, spread over four levels at 4500 square feet, only has eight rooms – a stair hall, sitting room/library, dining room, three en-suite bedrooms, and 2 servant rooms. This does not include service spaces like the basement kitchen, two pantries, storage rooms, and four full and two half bathrooms.

Front door and vestibule of the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Looking through the vestibule’s original stained glass into the entry hall with mosaic fireplace. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Charnley’s entry hall with its concealed staircase. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Looking up at the decorative wood panels of the second floor balustrade. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Close-up of the entry hall’s newel post, exhibiting typical Sullivanesque ornament. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The mosaic floor in Adler & Sullivan’s Schiller Building (1891) is strikingly similar to Charnley’s fireplace. [Photographer: John Vinci/Richard Nickel Archive]

The three-story central space of the Charnley House is entirely unique for a domestic building, similar to the large enclosed light wells of late 19th century office buildings like Burnham & Root’s Rookery or even communal spaces like the Mecca Apartments, built at the same time as Charnley. The vertical atrium, later adapted by Wright in his Larkin Building (1903-06) and Unity Temple (1905-08), greatly contrasts the strong rectilinearity of the home’s facade. Charnley’s inside space is also elevated with three pairs of arches, while no doors separate the rooms.

Charnley’s three-story atrium is similar to the skylight interior court of the Mecca Apartments on Chicago’s South Side. Both buildings date from 1891. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns and Mecca Flat Blues exhibit]

The vertical spaces inside Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building in Buffalo and Unity Temple in Oak Park. [Ryerson and Burnham Libraries/Modern Illinois]

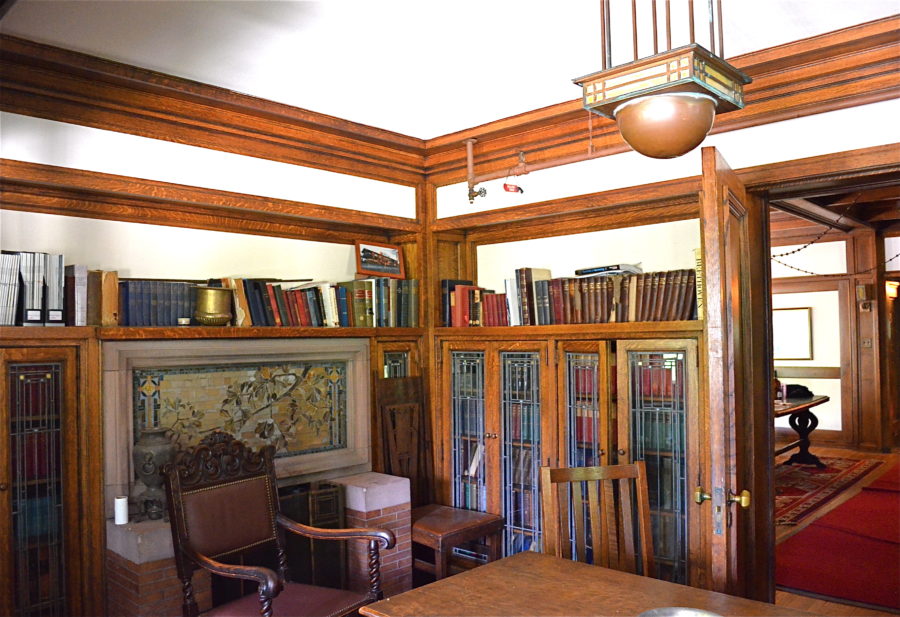

The Charnley House library. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The Charnley dining room. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Close-up of the mahogany fireplace mantel in the dining room, which exhibits Sullivan’s seed pod motif. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Frank Lloyd Wright probably had a hand in the details of the living room fireplace. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The main staircase of the Charnley House is hidden behind a wall and entered through a large arch, an idea “borrowed” from H.H. Richardson’s Glessner House (1885) on Chicago’s Prairie Avenue. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Richardson’s Glessner House. [John Foreman/BIG OLD HOUSES]

Close-up of the main staircase with dental trim under each step. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Walking down from the second level, one can see the home’s geometric patterns in the stair stringer, beaded spindles, and jig saw decorative panels of flat foliage. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The most striking feature on the second floor is the wood screen/grill. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Natural light shines down on the wood screen/grill. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The balcony was the only outdoor space in the Charnley House, making it a true city residence. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The William Winslow House, Wright’s first independent commission. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

Winslow House

While still employed by Adler & Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright continued to create buildings either influenced by his first employer Joseph Lyman Silsbee or historical revival designs. It was not until he left Sullivan’s office in the spring of 1893 that Wright started to use Sullivan as a model of inspiration, evident in his first official independent commission, the William Winslow House in suburban River Forest, designed in March of 1894, nearly three years after the Charnley House. Winslow marked a transition for the young architect as he was memorializing where he came from and where he was heading simultaneously.

Winslow sits outside the coach house while his family poses in the arches of the inglenook. [Prairie School Review]

Winslow’s outlined stone entrance. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

Close-up of Winslow frieze in comparison with the one at the Dana-Thomas House (1902-04) in Springfield, IL. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns] [Courtesy of Stan Ecklund]

The rear of the Winslow House. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

The fireplace inglenook at the Winslow House. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

The arcaded loggia at Adler & Sullivan’s Schiller Building is strikingly similar to the arches of the Winslow inglenook. [Richard Nickel Archive] [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

A series of arches separate the living room from the dining room. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

The Charnley House front door, on the left, must have inspired Wright when he created Winslow’s front door three years later. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The Winslow library/study. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

Winslow’s wood screen on the second floor echoes the one found at the Charnley House. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

Looking down from the third floor through the octagon-shaped opening in the stairs. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

A Closer Look at the Babson and Bradley Houses

Even after the dissolution of his partnership with Dankmar Adler in July of 1895 , Louis Sullivan continued to work on domestic commissions. A number of these designs, including the Henry Babson House (1907-08) in Riverside, Illinois and the Harold C. Bradley House (1909) in Madison, Wisconsin, expand upon the design principles first established at the Charnley House. Some historians, like David Van Zanten, believe Sullivan’s 20th century homes, once dismissed, are just as important as Sullivan’s jewel box banks. He believes they expand upon the “spatial coordination of his theater model” in a more “horizontal” manner. While historians, like Narciso G. Menocal, theorize that “his houses…although they are excellent as works of art in the abstract, almost none of them functioned efficiently as family dwellings.” Why have Sullivan’s homes been so disregarded? Was he truly a failure as a residential architect as Menocal wants us to believe?

Sullivan’s Henry Babson House in suburban Riverside, before its demolition in 1960. [Richard Nickel Archive]

Unlike his brother’s own home, the Frederick Babson House, designed in 1907 by Tallmadge & Watson, survives in Riverside. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Photographs from The Brickbuilder, an American magazine on architecture and building, from 1910.

The exterior of Sullivan’s Babson House resembles a characteristic Prairie Style design with its dominant horizontal lines, broad eaves and low-pitched roof. The cantilevered arcaded loggia on the second level and the fretwork on the spandrel panels not only resembles Charnley but other Sullivan buildings as well. Unfortunately the residence was demolished in 1960 to build a new subdivision. After removing ornament and disassembling the balcony, photographer and historic preservationist Richard Nickel recalled returning to the Babson House two weeks later to find it completely flattened.

The Babson House during its demolition in 1960. [Richard Nickel Archive]

One of Sullivan’s few remaining residential designs, the Harold C. Bradley House, in Madison, Wisconsin. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Close-up of Bradley House ornament. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The entrance hall of the Bradley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

The Bradley House library has built-in bookcases and a mosaic fireplace, both similar to the interior of Charnley House. Also both homes share an emphasis on wood trim. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

If Sullivan was a failure as a residential architect, then who says Wright wasn’t as well? Charnley is not any more domestic than Sullivan’s later residential commissions simply because of Wright’s role. I have spent over a decade working inside Charnley as well as a number of Wright homes. Although beautiful, these buildings are completely impractical as single-family-homes, whether they are the work of Sullivan or Wright. And who says Sullivan failed? Just because the original clients, like the Bradleys, did not like it? Who says another family couldn’t have moved in and loved it? Sullivan designed nearly sixty residences in the 1880s and 90s. He obviously knew what he was doing.

The staircase of the Bradley House has a similar spindled wood screen to the one found in the Charnley House. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

According to Van Zanten, “the entrance-study cross-volume that increasingly appears in Sullivan’s layouts is a consistent elaboration of a processional construction in Sullivan’s interiors that makes them the opposite of Wright’s schemes.” Like his flowing ornamentation, Sullivan’s goal was movement through a geometric mass. The Babson and Bradley Houses are a continuation of the theme that began over a decade earlier in the design for Charnley.

Portraits of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, both taken in 1920. [Buffalo Architecture & History/Wisconsin Historical Society]

The Final Days

Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright were “so psychologically intertwined that an eventual reunion was inevitable.” The teens and twenties were difficult times for both men: Sullivan’s career dwindled while Wright’s personal life was in shambles. After abandoning his wife and six children in 1909, Wright became a social pariah. He experienced the devastation of losing both his beloved home in Wisconsin and mistress, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, in 1914. Wright was finally granted a divorce in 1922 only to see his home burn down a second time, find himself arrested and detained for violating the Mann Act, and have his career dry up.

A photograph of Wright’s arrest in Lake Minnetonka, Minnesota in 1926. [Minneapolis Star Tribune]

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Cedar Street Studio, where he lived and worked from 1914-15, was demolished for a similar-structure seen on the right in 2011. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Lessing Annex Apartments, circa 1911. [LakeView Historical Chronicles]

By 1905, Sullivan was living in a seedy apartment in the Lessing Annex Building (now the Commodore Apartments) at Broadway and Surf. Although his Ocean Springs cottage, mentioned in Part 2, gave Sullivan a sense of identity, the financial crisis of 1907 forced him into bankruptcy and, over the next few years, Sullivan was forced to sell his cottage as well as all his architectural library, art, and household goods. In 1909, the same year George Elmslie finally left his employment, Sullivan moved from the Auditorium Tower, where he had worked since the building originally opened in 1889, to cheaper rooms down below. Commissions had dried up. During this time three out of five residential projects were completely rejected by their clients.

Advertisement for the auction of Sullivan’s “valuable Architectural Library” and the Hotel Warner, where Sullivan lived the last decade of his life. [Chicago History Online/Illinois Digital Archives]

Sullivan’s writing desk, where he worked on Kindergarten Chats, survives at the Cliff Dwellers Club. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Wright recalled Sullivan’s final day – “He begged me to stay and died the after I had left him with nothing left in the world, except a beautiful old daguerreotype of himself, aged 9, with his mother and brother.”

Sullivan’s grave at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Neutra and Schindler

In the examination of the final days of Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan’s relationship, it is worth noting that two future modernist architects, Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler, were both part of their lives during this time period.

Modernist architect Richard Neutra left Europe for the New World in October 1923, first arriving in New York City before making his way to Chicago to see firsthand the Wright and Sullivan buildings that so inspired him. Appalled and fascinated by the crime-infested, smelly city, Neutra described Chicago as “a fat, dirty, healthy child with great potential.” Having personally observed the abstract work of Adolf Loos, Erich Mendelsohn, and Mies van der Rohe back in Europe, Neutra’s pilgrimage to see Wright’s Prairie Houses left him disillusioned as he found them “retardataire” and “dated” yet he still desired to meet Wright in person.

Neutra also visited all of Sullivan’s Chicago buildings, which left a lasting impression. “Here in the middle of North America, I thought was work which could be compared with what Otto Wagner had been doing in Vienna of Central Europe. And that was the very highest accolade I was capable of giving to anything built.” Wasting no time Neutra sought out the depressed and ailing Louis Sullivan, living on the edge of poverty in a run-down South Side hotel. Neutra assured the architect that his work had not been forgotten. Sullivan’s reply: “Perhaps in Sweden and Germany but not here [United States].”

Richard Neutra, standing behind his wife Dione Niedermann and their son Frank (named after Frank Lloyd Wright), and Rudolph Schindler the day the family arrived at Schindler’s Kings Road House in West Hollywood on March 7, 1925. [UC-Santa Barbara, University Art Museum, R. M. Schindler Collection]

Schindler had arrived in Chicago a decade before Neutra in 1914. He had left his native Austria with the intention to work for Frank Lloyd Wright. Although he met the famed architect that year, Schindler had to wait until 1918 before he was officially hired. In the meantime, Schindler, then living at Wright’s Oak Park Home & Studio, invited Sullivan for a personal visit. Sullivan’s letter accepting the invitation was found amongst Schindler’s possessions when he died in 1953.

[UC-Santa Barbara Art Museum/Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians]

Schindler’s wife, Pauline Gibling, whom he had met at Jane Addam’s Hull House in 1919, described Sullivan “as no longer active in architecture but living in a diminished fashion, sitting for hours in melancholy contemplation at the Cliff Dwellers Club.” In Sullivan’s desperate attempt to find a publisher for Kindergarten Chats, Schindler had offered to ask his mentor and Sullivan admirer Adolf Loos for help. Sullivan entrusted Schindler with his only copy of the manuscript, where it eventually ended up in the hands of Richard Neutra, still living in Austria at the time. Shortly after his move to Chicago three years later in 1923, Neutra recalled how difficult it was to still find a publisher for Sullivan’s Kindergarten Chats:

“I also talked to a few people in Chicago about it, and they all laughed at me. Sullivan? they asked, – isn’t he that old drunkard? He’s a pauper now, and is being supported by his friends; each one pitches in five dollars a month.”

Schindler continued Wright’s American operations while Wright worked in Japan on the Imperial Hotel. He later followed Wright to Los Angeles to work on commissions like Wright’s California block houses, but he found the architect to be “devoid of consideration and has a blind spot for regarding the qualities of other people.” Schindler felt underpaid and exploited as Wright’s employee.

When Schindler finally applied for his professional architectural license in 1929, he described his extensive work on the architectural and structural plans of the Imperial Hotel and being “in charge of the architectural office of Frank Lloyd Wright for two years during his absence.” Wright refused to validate these claims. He wrote to Schindler, “Nobody makes designs for me. Sometimes, if they are in luck, or rather if I am in luck, they make them with me.” Schindler countered Wright’s denials:

“The savage intensity, with which you repudiate all suggestion that somebody might even have been of use to you proves your debt. Even the Almighty seems in need of some angels or saints at times.”

Their relationship completely broke down by 1931 and they never reconciled, echoing Wright’s earlier fracture with his assistant Marion Mahony Griffin and her husband Walter two decades earlier.

The Charnley House, not long after its completion in 1892. [Burnham and Ryerson Libraries]

Conclusion

Although the debate over the Charnley House’s authorship will continue as long as there are architects and architectural historians, I hope this series has added a refreshing angle to the dialogue. We’ll never know who designed Charnley. But the mythologizing of Wright needs to stop. It’s been going on for decades and decades. Architectural historian Grant Carpenter Manson wrote in his 1958 book “Frank Lloyd Wright to 1910: The First Golden Age” that Wright and Sullivan were “of equal stature” and that “any influence flow(ed) more in Sullivan’s direction than in Wright’s.” In 1960 historian Vincent Scully declared that “Wright, at 22, was already more abstract than his predecessor.” Really? Have Scully and I looked at the same buildings? Because I strongly disagree.

Then you have Hugh Morrison, who contradicts himself in the monograph Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture, from one sentence to the next – “Students familiar with Wright’s developed ‘prairie style’ of the early 1900s find it hard to believe that this [Charnley] is one of his designs, since it has so many qualities of formal symmetry, monumentality, and sheer height that are completely lacking in his later work, together with undeniable Sullivanesque features. But a comparison (of this house with others) leaves little doubt that the Charnley residence may be considered a very early work of Frank Lloyd Wright.” Published a few years after Wright’s autobiography, Morrison validated Wright’s claims of Charnley authorship, which would go unquestioned for the next fifty years.

Charnley’s second level hasn’t changed as one can see in the photo on the left, taken in the 1960s, compared to the present day. [Richard Nickel Archive] [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

Beginning with the Ryerson Tomb, which was designed before Wright joined the firm, Sullivan grew as an architect during his experimental period between 1887-1890. The Charnley House fits perfectly with the evolution of Sullivan’s personal and modernist style. There was nothing in Wright’s work at this time, as I mentioned in Part 1, to suggest he was capable of creating a building of such geometric clarity and total abstraction like Charnley. It was only after Charnley’s completion that Wright’s work began to resemble the characteristics of the home’s design, as I discussed earlier with the Winslow House.

Let’s not forget Wright had little publicity prior to 1910. Chicago’s major architectural journal between 1883-1908, the Inland Architect, was silent on the subject of Wright while Sullivan was considered to be the major influence of the new style, later to be called the Prairie School.

Hugh Downs interviews Frank Lloyd Wright (sitting in one of his personally designed chairs) on the set of NBC’s Conversations with Elder Wise Men in Chicago in 1953. [NBC/Getty Images]

But there was another motive behind selling himself. While a painter can go out and buy a canvas to create a piece of art or a musician can pick up an instrument to create a song, an architect needs a client in order to produce a physical building. Wright needed commissions, especially during the bleak part of his career in the 1920s and 30s. In An Autobiography he is making himself out to be greater than he actually was at the time he worked for Sullivan because he had to.

Let’s not forget Wright was an egocentric who had a tendency to embellish the truth. Wright would claim credit for not only the Auditorium but also the Wainwright Building, Chicago Stock Exchange, and the Schlesigner and Mayer Store. Why do we question his involvement with those buildings, but not when it comes to Charnley? Unfortunately Wright’s self-importance came at the expense of not only assistants like Mahony and Schindler but his own “Lieber Meister” Louis Sullivan.

Louis Sullivan, seated right, at the Cliff Dwellers Club around 1920. [Cliff Dwellers Club]

The same can be said for Mies van der Rohe, probably one of the world’s most famous modern architects. How would Mies’ design motifs have developed if he had not had the opportunity to work for Peter Behrens early in his career. Until that time, Mies was working in traditional styles. The entire modernist movement owes its development to Behrens as it wasn’t just Mies who worked for him, but Gropius and Le Corbusier as well. In a parallel with Sullivan, Behrens does not get the recognition that he deserves.

Looking the arch in the Charnley alcove – the circles of the front windows are reflected on the home’s back wall. [Rachel Freundt/Chicago Patterns]

And how would Sullivan have reacted to his former employee claiming credit for the Charnley design a decade after his death? Sullivan probably would not have been surprised when one reads the few surviving remarks Sullivan made on Wright’s character. But Sullivan took architectural appropriation very seriously. In 1900 architects, Tenbusch and Hill, had plagiarized one of Sullivan’s designs, specifically the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Duluth, Minnesota. Sullivan castigated them for their “unprincipled vulgarism” and “thievery,” and went on to write that “he [who] steals my art he steals my honor.”

Although the argument can be made that 1891 was the busiest time of Sullivan’s career as he had four major commercial buildings underway (plus three on board as well as the work for the World’s Columbian Exposition), whatever role Wright might have played, Sullivan’s contribution to the Charnley House should not be dismissed. As Wright biographer Brendan Gill dutifully noted in Many Masks, the relentless rigidity of the facade and its interior “bears Sullivan’s stamp.” The total emphasis on modern abstract forms and simplicity was part of Sullivan’s design process at the time, whereas Wright was still designing homes in historical revival styles. Sullivan’s close relationship with the Charnleys also cannot be dismissed. Besides the fact that Wright, who made misleading and self-serving statements during his entire career, only became attached to the home after Sullivan’s death. Wright might have been “a good pencil in [Sullivan’s] hand” but so were Irving Gill and George Elmslie. There would no pencil, or Wright for that matter, without Sullivan’s influence.

References

- Connely, William. Louis Sullivan as He Lived: The Shaping of American Architecture, a Biography. New York, Horizon Press, 1960.

- Hines, Thomas S. Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism: 1900-1970. New York: Rizzoli, 2010.

- Longstreth, Richard, ed. The Charnley House: Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Making of Chicago’s Gold Coast. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Menocal, Narciso G. Architecture As Nature: The Transcendentalist Idea of Louis Sullivan. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

- Neutra, Richard. Life and Shape. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962.

- O’Gorman, James F. Three American Architects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks and Peter Goessel, ed. Frank Lloyd Wright: Complete Works, Vol. 1, 1885-1916. Taschen, 2011.

- Severens, Kenneth W. Prairie School Review Volume XII, No. 3, June 1975.

- Twombly, Robert. Louis Sullivan: His Life & Work. University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Twomby, Robert. Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 1987.

This series has been absolutely fantastic, thank you.

Bravo!

Rachel, your work is amazing!

thank you for actually trying to interpret the physical evidence, which not many people do – but really,the art glass at the Blossom and Charnley house from a catalogue?? no – and most importantly, you overlooked how projects are accomplished in a large arch. firm. There is a partner, and project architect, just like sullivan and wright. They designed the house like any other project in the firm – not very complicated. You might try talking to people who actually worked on the house – sometimes they have insights!

Thanks for reading and commenting, John!

First of all, I work at Charnley-Persky as tour manager, and have done so for almost a decade. I’ve learned a lot about the home over the years.

In regards to the Blossom connection, I was told by Pauline and Anne about it and the possibility it could have come from a catalogue as its design was not something Wright or Sullivan would have done. If that’s wrong, I’m sorry but that what I had been told.

I don’t know if you read Part 1 or Part 2 of this series but I do go into the roles of a big architecture firm. I specifically discuss the possibility of both Irving Gill and George Elmslie and the roles they might have played in the firm. Comparing other projects Wright was attached to at the time, and their lack of “modernist” touches has led me to believe Charnley did not solely come from him as he claimed.

But lastly, the series was meant to lay out all the intrigue and controversy associated with the home’s design. Of course we’ll never know the absolute truth as I know a lot of original documents related to the home do not survive. But the fact that Wright only claimed he designed Charnley after Sullivan was dead and almost 40 years after the house was built is an important consideration when discussing who did what.

Was Wright at his full strengths when Charnley was designed? I think not. He was only 23 years old. Did Sullivan strongly believe in the “initial sketch” of a design and was known for being very hands-on? Absolutely. I think it’s about time Sullivan deserves some credit and recognition. He’s been overshadowed for too long by his mentee.

of course sullivan should be credited! You should probably talk to Tim Samuelson about the ornament on the art glass. He will show you other examples. Don’t forget Elmslie’s comments about Wright _ “I remember the morning that Frank brought in the 1/4 scales” referencing FLW working on the house in the evenings. I’m sure the massing, etc. was Sullivan’s, even some of the interior ornament, but I’m also sure he left it up to his employee FLW to complete the working drawings.

You forgot the last part of the quote, in which Wright said ‘George this house is the result of my training here.’ Elmslie said Sullivan ‘closely followed the progress of affairs.’

It’s interesting that Tim thinks the windows might be designed by Wright or Sullivan, although I have disagreed with him on a few things, like the possibility of Irving Gill’s role in Charnley’s design.

Thanks again for the comments! I will add/change the part about the Blossom windows as soon as possible.

Nice work. For much more on the story of “The Chats” see my “”R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra and Louis Sullivan’s ‘Kindergarten Chats'” at: https://socalarchhistory.blogspot.com/2011/05/r-m-schindler-richard-neutra-and-louis.html