A Brief History of Milwaukee Avenue: the Chicago School and Sullivanesque Style

The first part of this series looked at the early history of Milwaukee Avenue, and now we’re going to look at two related styles prevalent along the diagonal thoroughfare: the Chicago School and Sullivanesque.

Above is the Chicago School style, 1913 Holabird & Roche building at Milwaukee, North, and Damen.

The Chicago School (or Commercial Style) is frequently referred to as the architectural style that brought forth the earliest skyscrapers. This style was practiced by the firms of Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Holabird and Roche, and Burnham and Root.

The Sullivanesque style evolved in the late 1890s, growing out of inspiration from Adler & Sullivan’s grand creations. Some of its early practitioners were former employees of Adler & Sullivan’s firm and went on to create landmarks and icons espousing the principles of the firm.

But by the 1920s, the Sullivanesque architectural style quietly morphed into to a regional design pattern, one of many choices for economical facade design.

Before exploring the impact of Sullivanesque and the Chicago School of architecture on Milwaukee Avenue, let’s briefly examine the evolution and history of both.

Chicago School and the Commercial Style

Commercial architecture is the just title to be applied to the great airy buildings of the present. They are truly American architecture in conception and utility. The style is a monument to the advance of Chicago in commerce and commercial greatness and to the prevailing penchant for casting out art where it interferes with the useful. It is a commanding style without being venerable. […] The commercial style, if structurally ornament, becomes architectural.

—Industrial Chicago, 1891 [p. 70]

A Design Constraint Imposed by the Great Fire

The Chicago School loosely refers to a style and the group of architects that arose in the years after the Great Fire.

Just before the 1871 fire, roughly 2/3 of the city’s building stock consisted of wooden structures, many of them built in haste and without much attention to durability and fire resistance. After the Great Fire, laws required construction with fire resistant materials.

The new commercial building style crafted innovative designs with familiar materials. Later breakthroughs in construction methods gave rise to a style with equal amounts of function and form. A somewhat synonymous term for Chicago School architecture is Commercial Style.

With land prices and demand for more space increasing, the fervent economic activity and building boom in the years after the Fire expedited this new style.

Jenney and the Evolutionary Skeleton Frame

After the Fire, the 1880s saw a wave of buildings and the incorporation of a structural technique which would influence the overall appearance.

An early example of this architectural evolution was the First Leiter Building at Monroe and Wells (no longer extant), in which interior and roof loads were supported by cast-iron columns.

The full evolution of this technique arrived with the 1884 Home Insurance Building, eloquently described by the late architecture and urban planning historian Carl Condit:

Whatever the source, the major step in the conversion of a building from a crustacean with its armor of stone to a vertebrate clothed only in a light skin occurred in the two years following 1883, when Jenney received the commission for the Chicago office of the Home Insurance Company.

–Carl Condit, The Chicago School of Architecture

Until William Le Baron Jenney’s innovations in load-bearing skeletal frames, the height of a building had a fixed limit imposed by its construction material. The thickness of load-bearing masonry walls must increase with proportion to its height, which set a limit of about 10 stories. However, Jenney’s breakthrough technique would give way to the world’s first skyscrapers.

Jenney would also play an important role in architectural history by inviting a young Louis Sullivan to join his firm in 1873.

Common Thread of Modernism and the Chicago School: Sullivan

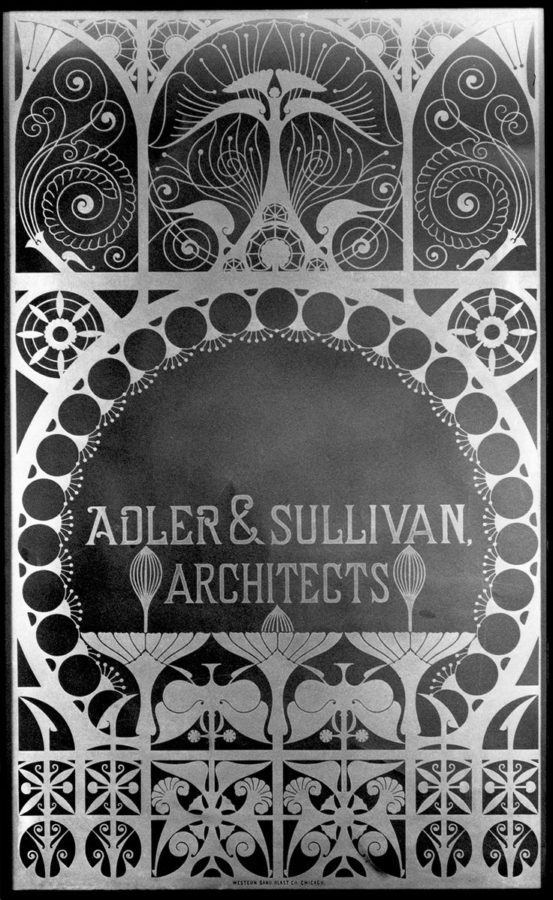

The architectural styles featured in this part of our Milwaukee Avenue tour–Chicago School, Prairie School, and Sullivanesque–trace back to Louis Sullivan. After leaving Le Baron’s firm, Sullivan joined Dankmar Adler, forming a new firm: Adler & Sullivan.

The Chicago School and Prairie School were often directly or indirectly inspired by Sullivan. Sullivanesque more completely embodies the geometric and organic nature of his work, though in many cases it’s mostly in the form of applied ornament.

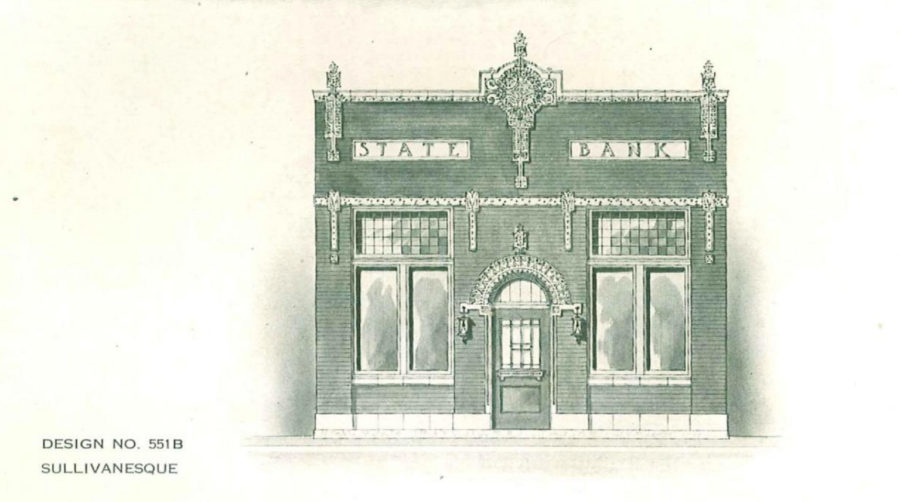

As an architectural style, Sullivanesque describes Sullivan’s work or that of his former employees or encompasses a later period of work in which stock terra cotta replicas of his designs were used without his consent or endorsement.

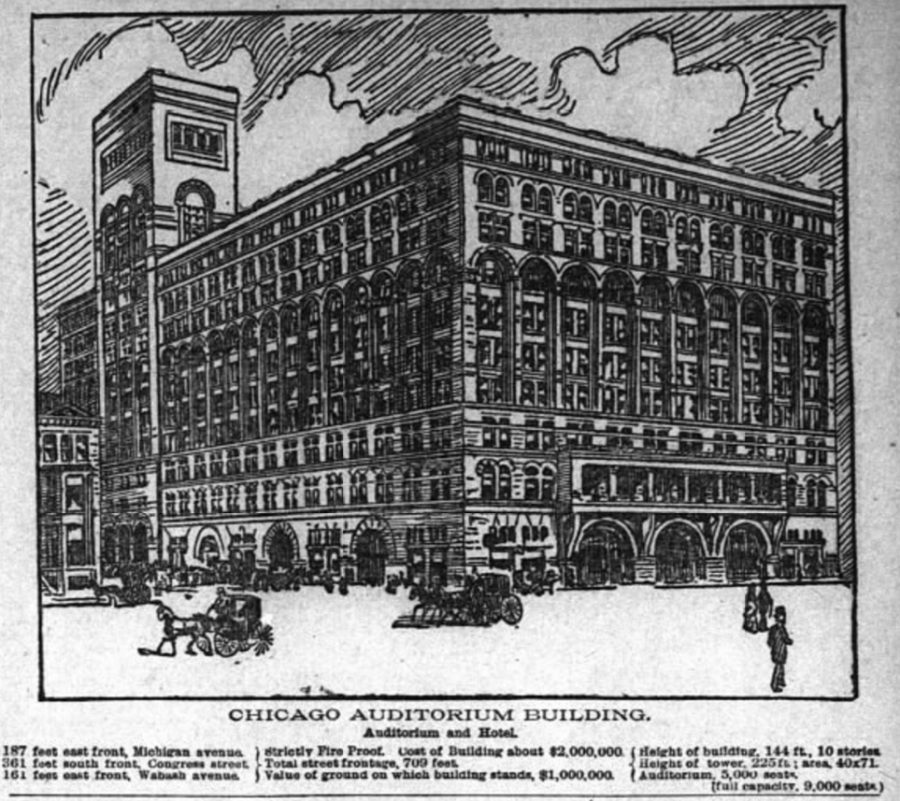

Announcing Adler & Sullivan’s new Auditorium Building, Chicago Inter Ocean, July 10, 1887

First Phase: Ascent and Monumental Commissions (1883-1910)

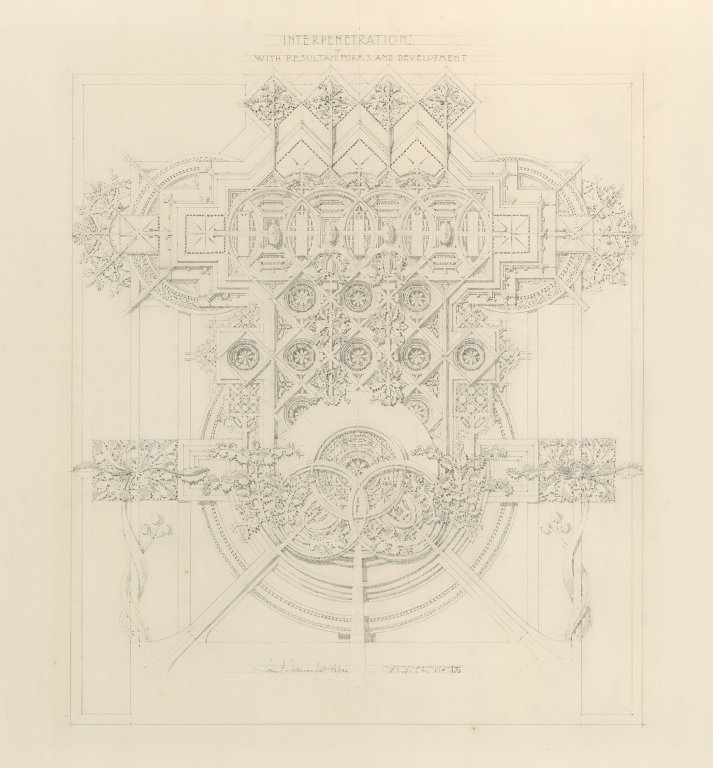

Sullivan’s mastery of blending organic forms with geometry ushered in an era in which architecture emphasized forms and ornament not revived from the past. His early work in large scale commercial buildings is often grouped under the Chicago School style while his later smaller projects are grouped under Prairie School.

The Panic of 1893, initiated by shoddy banking practices, gutted the firm of Adler & Sullivan. The firm’s staff of 50 was suddenly pared down to the two original principals. With work dwindling, Adler left for a short stint as an engineering consultant for an elevator company.

Though Adler returned to architecture not long after, Sullivan rebuffed his attempt at rejoining the firm. The two remained in contact and collaborated on the Carson Pirie Scott & Co. building (1903), but the official partnership never resumed.

Perhaps because he lacked Adler’s business development expertise and interpersonal skills, Sullivan wasn’t able to resurrect his practice. The firm went on to rapidly decline without his former business partner. Sullivan’s commissions after the Carson Pirie and Scott Building were for much smaller building projects, based mostly outside of Chicago.

Second Phase: Sullivan’s decline and the Arrival of Midland Terra Cotta (1911-1930)

From the mid-1910s to early 1920s, Sullivan’s commissions were very few and far between. He could barely keep himself fed and sheltered, often relying on the charity of fellow architects and former employees that held him in high esteem. One of these former employees, Frank Lloyd Wright, would correspond via letters and offer small amounts of financial assistance.

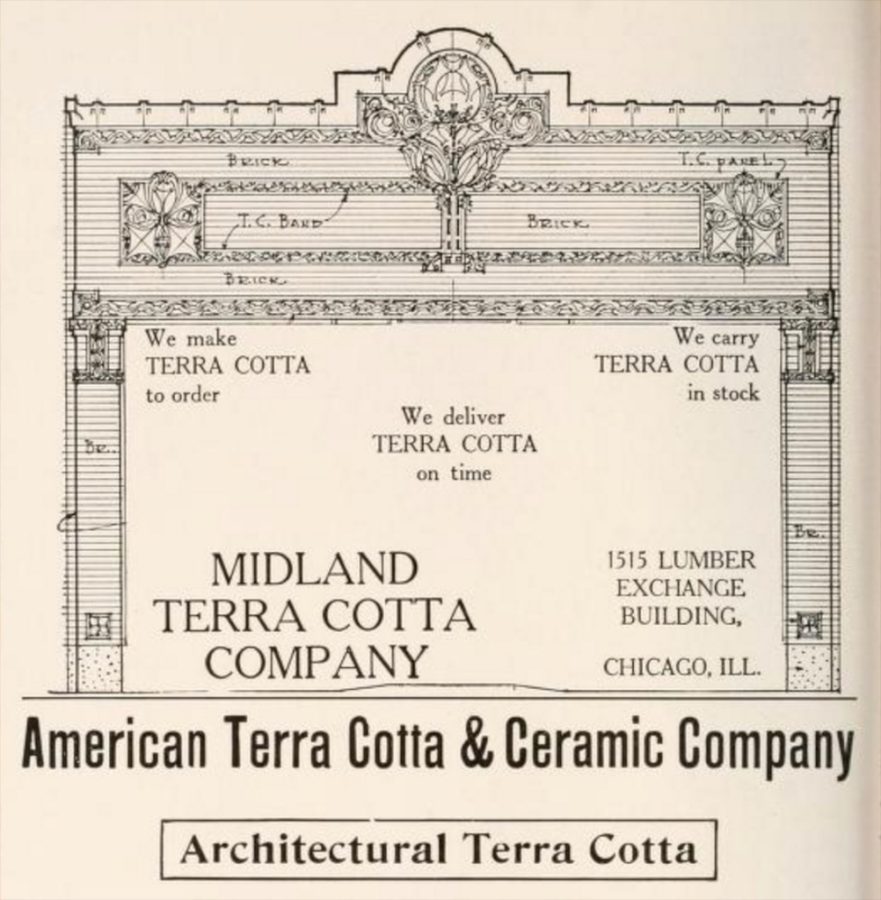

As Sullivan’s career began a downward fall after the turn of the century, his work received renewed attention when the Midland Terra Cotta company began making architectural ornament in 1911. In many cases, design options in pattern book catalogs would list a particular style as Sullivanesque.

Sullivan detested the pattern book designs which used his name, which he viewed as a watered down replication of his work. He received no royalties from the companies that used his name and style.

In these pattern book designs, Sullivanesque existed as a specific trim option for vernacular commercial architecture. Stock terra cotta provided a way for buildings which normally wouldn’t have a budget for detailed ornament to elevate their stature and appearance.

Using stock Midland Terra Cotta company plates and plans, architects outside of Chicago spread the pattern-book variant of the style. From Illinois cities like Rockford and Galesburg to out-of-state areas like Cleveland, Detroit, Grand Rapids, and Kalamazoo, buildings featuring geometric ornament and decorative terra cotta were going up throughout the Midwest. Midland also influenced terra cotta companies in cities like St. Louis to produce Sullivanesque decorative components.

Minnesota showed a more direct embrace of Sullivan’s style. Two Minneapolis firms which held Sullivan in high regard adopted his design aesthetic, as well as the public’s general admiration for Sullivan’s Owatonna Bank (1908).

In the mid-to-early 1920s, the style fell from the imagination of clients outside Chicago. It would persist in Chicago, but only for a few more years.

Sullivan’s Organic and Mathematical Universe Becomes Dim

Although penniless near the end of his life, Sullivan still wielded influence in the architecture world. His words appeared in architecture publications, and he published two works defining his legacy for posterity. The Autobiography of an Idea (1924) examines the origins of his fascination with nature and design and catalogues his achievements in buildings and philosophy. In System of Architectural Ornament (1922), 20 plates and a manuscript illustrate how Sullivan reconciled science, nature and design. In 1924, Sullivan died a week after receiving published copies of his final two works.

After his passing, architects would create works of art that were either directly or indirectly influenced by him for many more years.

The combination of high style and vernacular buildings left us with a city dotted with architectural gems that illustrate the relationship between mathematical and organic forces of nature.

Now that we’ve reviewed a little architectural history, let’s explore Sullivanesque and Chicago School architecture on Milwaukee Avenue from city center out to Jefferson Park.

Milwaukee Avenue: Pattern Book Sullivanesque

1012 N. Milwaukee, J.J. Cerny, 1925

The first stop in the Sullivanesque and Chicago tour is 1012 N. Milwaukee in Noble Square.

This building was built in 1925 and designed by architect J.J. Cerny. Cerny didn’t adhere to one particular style. Instead, he built a number of small residential and commercial buildings in various styles. One of his larger commissions was the Freeman Landon House in Oak Park which features elements of Colonial Revival and the Prairie School.

1012 N. Milwaukee was once home to Empire Coin Machine Exchange, a manufacturer and distributor of games, including pinball. A 1951 ad for Old Hilltop in Billboard Magazine shows a game they may have designed.

Rissman & Hirschfield, 1922. 3015 N. Milwaukee [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Chicago Tribune, August 26th, 1923

It was originally the Milmount Drug Store as written in the article detailing a robbery above. It later became Kowalski Pharmacy. Today it is home to Physicians Care Center.

Parapet detail, 3015 N. Milwaukee [John Morris]

3255-3261 N. Milwaukee, A.M. Ruttenberg, 1925

Contrasting Architectural Styles

While most of the stock terra cotta buildings that feature Sullivanesque ornament were “modernistic,” an interesting exception is at 3261-3265 N. Milwaukee. The architect of the two joined buildings was A.M. Ruttenberg, known for designing buildings in varying eclectic styles, such as Classical and Renaissance Revival.

Kozy Cyclery [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Entrance terra cotta surround in Neoclassical form [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Top terra cotta: Sullivan’s disc on the parapet.

4257 N. Milwaukee, Levy & Klein 1922/23 [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Mirrored Twins

4257 N. Milwaukee features a two identical buildings that mirror one another.

4257 N. Milwaukee [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

4412 North Milwaukee. James Guske, 1922 [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Sullivanesque an an Afterthought

In some cases, a store and flat building can appear plain and unremarkable until one takes a closer look. This is evident at 4412 N. Milwaukee.

4412 N. Milwaukee [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Edward Fox Photography Studio in early 2015 [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Once Covered, Sullivanesque Detail Revealed

A move by Edward Fox Photography Studio in 2015 from their Milwaukee Avenue location revealed a Sullivanesque building long covered by a 1970s alteration. Sadly that alteration covered and destroyed some of the original ornament.

4902 North Milwaukee in February 2017. Jens J. Jensen, 1922. Kneipp & Kneggel Stores [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

The neighboring commercial property at 4900 N. Milwaukee Ave., where Edward Fox Photography was once located, is part of a mixed-use project that calls for second- and third-floor additions with a total of six living units. A construction permit for the project was issued in November.

But a month after that report, Nadig reported that plans may be expanded:

A construction permit allowing construction of six apartments and storefronts was issued for the site last fall, but the project reportedly may be expanded. Brugh said that the developer is expected to submit revised plans.

It’s unknown how much, if any, of the original structure will remain in the new building. The 1970s-era gravel composite wall and wood shingles were removed, exposing the original terra cotta below. From the outside, it appears much of the ornament was permanently destroyed or lost when the building was altered. Hopefully, the restored structure will incorporate restored historic Sullivanesque detailing.

J & R Sone Stores. Wm Schulze, 1922 [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Small Sullivanesque panels on the Nadig Newspapers building in Jefferson Park [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

4956 N. Milwaukee, Jens J Jensen, 1922 [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

4956-4958 N. Milwaukee

Architect Jens J. Jensen–no relation to the landscape architect–constructed at least two Sullivanesque buildings in Jefferson Park. The first is the former Edward Fox Photography Studio, the other at 4956 N. Milwaukee (above) for Andrews Realty Company in 1922.

There are no clues in the 1922 American Contractor publication announcing the new building. Various ads in the 1950s, 1970s, and more recently indicated its frequent purpose as a liquor store. Today it is home to The Clubhouse, a resource for speech and occupational therapy.

[John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

[Detail, 4956-4958 N. Milwaukee. John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Milwaukee Avenue: Chicago School, Prairie School, and High Sullivanesque

1579 N. Milwaukee, designed by Holabird and Roche [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

At the time of its construction, it housed retail on the ground floor and offices on the upper floors, similar to its use today. Today, the building also houses artist studios and spaces.

The three floors create a labyrinth of studios where a new surprise can be found around every corner. During both daytime and nighttime the building is open to the public. Guests are free to check out the building and explore what it has to offer. Many nights there are art events happening, performances, and open studio events.

Carl Schurz High School [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Carl Schurz High School

As one continues to travel northwest on Milwaukee Avenue, the buildings become lower and farther apart. At Addison and Milwaukee, the landmark and city treasure Carl Schurz High School stands alone, towering over trees and airy space.

As described in Part 1, An Indian Trail Becomes Dinner Pail Avenue, Schurz was built to accommodate an expanding immigrant population:

As more immigrants from other countries arrived along Milwaukee Avenue, early German arrivals forged a path to the northwest toward suburban or rural areas. One destination on this path was Irving Park. The arrival of Germans (along with the Swedes) tripled the population between 1910 and 1920–from 14,748 to 42,467.

One of the remnants of this rapid expansion is the nationally landmarked Carl Schurz High School at Milwaukee and Addison.

An expanding population needed a larger school, and Carl Schurz would be the namesake for the new school. Schurz, a German immigrant, had no connection to Chicago but was a General in the Civil War, a Senator, and Secretary of the Interior, among other titles.

Designed by Dwight Perkins, this near-perfectly preserved structure represents a blending of the Chicago School and Prairie School styles of architecture. Today, roughly 1,200 students are enrolled.

Carl Schurz High School [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

With Schurz High School, architect Dwight Perkins used geometrically stylized columns that also demonstrated function. The use of brick, terra cotta, and stone seem to flow from the inside out, giving each material quality and purpose, and not simply a cosmetic addition.

Library, former auditorium in Schurz High School [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

The Auditorium Becomes Quiet

In an odd twist of fate, the part of school designed to amplify and carry sound is now used for a traditionally quiet space. The expansion in the 1930s saw a new auditorium, and the previous gathering space became the library.

In 1941, students and muralist Gustav Brand designed and painted the new library’s ceiling murals. Brand arrived in Chicago from Germany in 1892 to complete murals for the Germany Exhibition Hall at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

The murals depict the evolution of the printed word from prehistoric times leading up to the printing press. The murals were painstakingly restored in 1997-1998.

Schurz Auditorium [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Behind the curtain in the photo above is the massive Möller pipe organ. The organ contains 45 ranks and 2934 pipes, making it roughly one-third the size of the largest pipe organ in the midwest at Fourth Presbyterian Church.

1925 Peoples Gas Irving Park Neighborhood Store, designed by George Grant Elmslie and Hermann V. von Holst. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Irving Park Peoples Gas Store

Erected by Peoples Gas in 1925 when electricity began to replace natural gas use in the home, the Irving Park Peoples Gas Store showcased gas-powered appliances to highlight the relevance and utility of the natural resource. Large plate glass windows offered passersby a view of the goods inside.

Peoples Gas Store detail [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

A Strong Statement in a Fading Style

George Elmslie worked for Louis Sullivan for twenty years, starting as a draftsman for the firm of Adler & Sullivan. Sullivan inspired a number of architects that launched successful careers. Elmslie may have embraced his former employer’s ideals the most. But rather than copy and place motifs into his own works, Elmslie built on Sullivan’s ideas of geometry and nature with his own style, appropriate for the commission and context.

By 1925, Sullivan’s influence had long faded from the imagination of the public and architectural community. Even the watered-down pattern book variety of Sullivanesque was on the wane. Revivalist forms such as Gothic Revival re-emerged, as did prototypical modernist forms such as Art Moderne, largely made possible by Sullivan.

In the face of changing tastes, Elmslie designed a structure that fully endorsed his former master’s ideals. The use of repeating V motifs, art glass, and an emphasis of the vertical and horizontal are at least partly reminiscent of Sullivan, but bears Elmslie’s own personality.

A building seen as a company’s reaction to modern consumption trends (the widespread arrival of electricity in the home) fully embraced past glory–via its Sullivanesque design.

Pointed roof over one-time auditorium visible in top left [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

The Forgotten Auditorium

The Peoples Gas store also housed a 350-seat auditorium. The building’s top floor was originally planned to host home economics classes to provide instruction on how to use the appliances sold at the store.

The City of Chicago Landmark Designation Report further details the forgotten Prairie School gathering place:

Although not visible from the street, the ceiling directly over the auditorium area was raised to a high gable earned by exposed steel trusses spanning the full width of the building. Original drawings indicate that the upper walls were simply finished with plaster and wood trim, and that a lunette formed over the stage platform was decorated with a mural painting. Natural light from the large front windows was augmented by skylights with art-glass panels at ceiling level. The upper ceiling area is now completely obscured by a dropped ceiling.

At the time of the designation report’s publish date (1985), it continued to operate as a Peoples Gas retail store. More recently it was home to Slingshots Teen Center.

It’s located at 4839 W. Irving Park Road, just off of Milwaukee Avenue.

Milwaukee Avenue after Sullivanesque

After expansion beyond Chicago into far flung areas of the midwest, the style of pattern-book Sullivanesque with stock terra cotta faded much in the same way it arrived: present as an afterthought in small construction projects in Chicago. By the late 1920s the distinctive Sullivanesque geometric and organic terra cotta ornament was absent from all new construction projects. The related and highly refined styles of the Chicago School and Prairie School were also fading from the imagination of practicing architects.

The arrival of the Great Depression and lack of new construction that came with it ensured these architectural styles native to Chicago were fully extinguished.

Art Deco ornament at Montrose and Milwaukee [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Transition to Art Deco and the Machine Age

In the 1920s as the styles largely inspired by Louis Sullivan were in descent, another one became ascendant: Modernistic, an ambiguous label applied to many architectural styles over the course of successive generations. This particular type of modernism would later be known as one of its more specific types: Art Deco and Art Moderne/Streamline.

An era that started before the Great Depression and ended around the middle of the century brought eye-catching and futuristic design meant to surprise and delight. Milwaukee Avenue contains a showcase of Art Deco design large and small, which we’ll explore in part three of this series: A Brief History of Milwaukee Avenue: Art Deco and Machine Age Showcase.

Related Articles

- A Brief History of Milwaukee Avenue, Part 1: an Indian Trail Becomes Dinner Pail Avenue

- Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Charnley House, Part 1

References and Further Reading

- Sullivanesque: Urban Architecture and Ornamentation (Ronald E. Schmitt, 2007)

- The Chicago School of Architecture (Carl Condit, 1973)

- Peoples Gas Irving Park Neighborhood Office (Landmark Designation Report)

- Carl Schurz High School (Landmark Designation Report)

- Industrial Chicago

Leave a Reply