The Surviving Post-Fire Buildings in Chicago’s Loop

Lake-Franklin Group, viewed from northwest corner of Lake and Franklin Streets. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Post-Fire buildings’ architectural style is typically Italianate in varying degrees, and virtually identical to those destroyed in the fire. This is significant as it aesthetically forms a portal to the look of the “Pre-Fire” downtown Chicago building stock before it was completely obliterated. Functionally, the majority of the buildings served as wholesale commercial lofts, with each floor housing a different manufacturer of products appropriate for the era: leather goods, textiles, household amenities like pianos, steam heaters and boilers, and iron & woodworking machinery.

However, within a decade or two after they were built, these 4- and 5-story Victorian-era buildings quickly fell out of style, regarded as old-fashioned and obsolete in the rapid evolution of Chicago’s commercial architecture. Many were demolished within decades of their creation, to make way for larger, more efficient and spacious office-style buildings utilizing a steel and skeleton framework method.

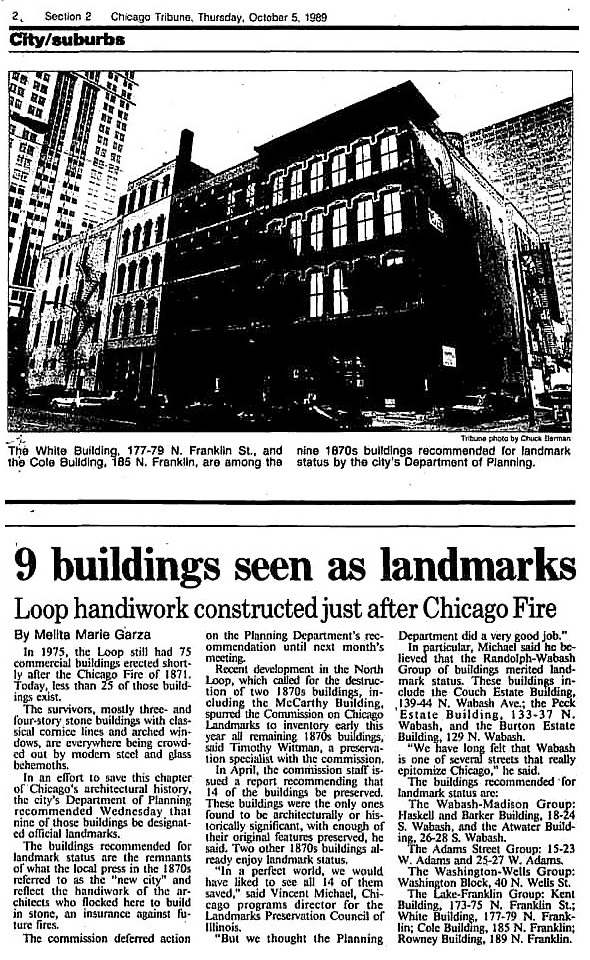

Excerpt of an October 1989 Chicago Tribune article detailing the City of Chicago’s landmarking process for collections of Post-Fire era buildings in the Loop. [Chicago Tribune]

Of these 21, only 10 are recognized and protected as Chicago Landmarks. Some of the other 11 are “orange-rated” (or recognized as “historically significant” in the Chicago Landmarks Historic Resources Survey [CHRS]), and a handful are not even “buildings” proper, but preserved façades with the original building demolished in recent redevelopment on the site. The rest hold no historic recognition, or even inclusion in the CHRS for unknown reasons. This article represents my attempt to document these remaining Post-Fire era “survivors”, spread out between the northwest corner of the Loop at Lake and Franklin Streets, down to the southeast at Adams Street and Wabash Avenue.

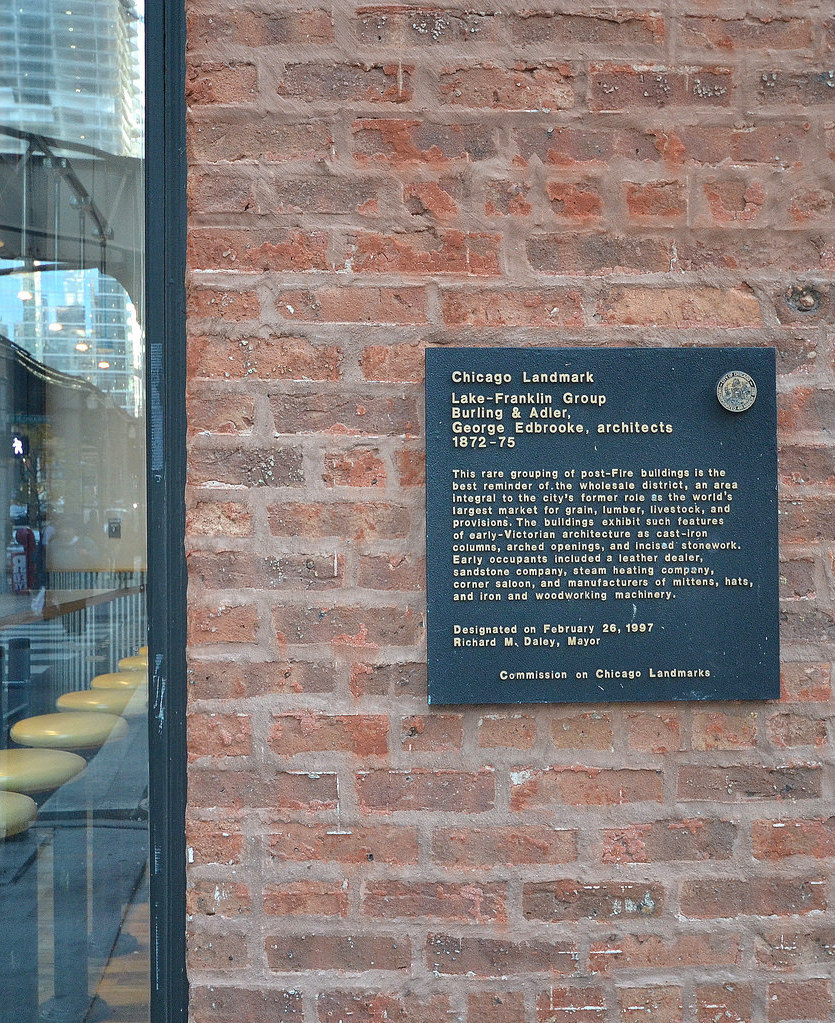

LAKE-FRANKLIN GROUP

Built 1872 – 1875

Kent Building, 173 – 175 North Franklin Street, built 1875 (George H. Edbrooke, architect)

White Building, 177 – 179 North Franklin Street / 227 – 231 West Lake Street, built 1872 (Burling & Adler, architects)

Cole Building, 185 North Franklin Street / 233 West Lake Street, built 1873 (Burling & Adler, architects)

Rowney Building, 189 North Franklin Street / 235 West Lake Street, built 1873 (Burling & Adler, architects)

Status: Protected by Landmark Designation on February 26, 1997

Plaque commemorating Lake-Franklin Group’s Chicago Landmark status, at the Rowney Building, 189 North Franklin Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

North elevation, Lake-Franklin Group: 227 – 235 West Lake Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

North elevation, Lake-Franklin Group: 227 – 235 West Lake Street (223 West Lake Street in white terra cotta façade not included). [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

West elevation, Lake-Franklin Group: 173 – 189 North Franklin Street [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Osborne & Adams Leather Company Building

209 West Lake Street

Built 1872 – 1874 (estimated)

Status: Orange-Rated in the CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation, Demolition Imminent

Façade of 209 West Lake Street with cast-iron pillars, seen from ground level. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

During my visits to the Loop, walking east on Lake Street into downtown, I would always notice this curious building just two addresses east of the Lake-Franklin Group. It’s situated between a 3-story parking garage (now all but demolished) and the well-known, after-work spot Monk’s Pub. The cast-iron columns at ground-level painted in flashy, metallic silver seemed out of place, but provided a glimpse into the historic nature of the building (and its recent occupancy by a poorly-reviewed afterhours nightclub).

Out of nowhere in late August, in one of my regular checks of the City of Chicago’s Demolition Delay Hold List, I saw this address added and was immediately alarmed—I set out to find out as much as I could about the building’s history and significance.

209 West Lake Street, with Lake Street elevated rail in foreground. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

It has been suggested that this building was designed by John Mills Van Osdel, recognized as Chicago’s first architect. This would certainly give even greater significance to the Osborne & Adams Leather Company building, but at time of publication I was not able to find any historic documentation or evidence to support this claim—aside from very similar designs like his aforementioned McCarthy Building and other Post-Fire buildings to be explored later in this article.

detail of façade and window hood variations, 209 West Lake Street [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

rear of 209 West Lake Street, viewing northeast, with demolition of parking garage at 215 West Lake Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

As I continued to investigate this further, I sadly found that the building’s fate was all but sealed: plans were made public for a future 33-story apartment tower to replace this site and the adjacent parking garage to the west. Finally, after the mandated 90-day Demolition Delay review period had elapsed with no plans emerging to save the structure, a demolition permit was issued for its destruction.

Rear entrance with rectangular cast-iron pillars, 209 West Lake Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

203 West Lake Street / 186 North Wells Street

Built 1878 or earlier

Status: Not Included in CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Status

One address east from the 209 West Lake building is another post-Fire era commercial structure, with a different variation of the Italianate commercial loft style. Like the White and Cole buildings of the Lake-Franklin Group, the building is L-shaped with street frontage on both Wells and Lake Street.

186 North Wells Street (east elevation of 203 West Lake Street building). [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

The Wells Street elevation is faced with Chicago common brick dotted with rod tie support bolts, with rustic, dentiled brickwork above the cast-iron storefront, and flattened arch window hoods topped by keystones with a relief detail on the second and third stories. It currently houses the Crepe Bistro restaurant and bar.

Detail of second and third floor window bays with Italianate-style flattened arch window hoods, 186 North Wells Street (east elevation of 203 West Lake Street building). [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

detail of second and third story window bays, 203 West Lake Street (north elevation of 186 North Wells Street building). [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

WASHINGTON BLOCK

40 North Wells Street

Built 1873 (Frederick and Edward Baumann, architects)

Status: Protected by Landmark Designation on January 14, 1997

North elevation of Washington Block, viewed from the northwest corner of Washington and Wells Streets. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Situated at the southwest corner of Washington and Wells Streets, the 5-story Washington Block looks somewhat out of place among modern structures. When erected, it was one of the tallest buildings in the wake of the Great Chicago Fire, and is a remaining example of an “isolated pier foundation” which contributed to making Chicago the birthplace of the skyscraper.

The isolated pier technique employs several separate foundations, one at each of the load-bearing points beneath ground level. This revolutionary method allowed the Washington Block to be built on soft, compressible soil, instead of the solid bedrock once seen as a requirement.

![Plaque commemorating the landmark status of the Washington Block [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DSC_4673-1024x835.jpg)

Plaque commemorating the landmark status of the Washington Block [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Upper floors of the east elevation, Washington Block, 40 North Wells Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

DELAWARE BUILDING

36 West Randolph Street

Built 1872 (Wheelock and Thomas, architects)

Status: Protected by Landmark Designation on November 23, 1983

Contrasted with the sleek “Block 37” development across the street, the Delaware Building certainly stands out on the northeast corner of Randolph and Dearborn Streets. When originally built in 1872, the Delaware Building had five floors with a basement. The first two stories were made of metal and glass to provide attractive storefront windows for retail displays. In 1889, two additional floors were added, and three bays were removed from the Randolph Avenue façade.

West elevation, Delaware Building, 36 West Randolph Street, built 1872. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

This building is also notable and unique for its early use of a pre-cast concrete façade. It was designated a Chicago Landmark on November 23, 1983, and it was previously listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 18, 1974. A McDonalds currently takes up the ground-floor and second story. Other tenants including Fitzpatrick & Fitzpatrick, a law firm, and Guaranty National Title, whose executives are also owners of the building, reside in the upper floors. A foreclosure lawsuit was brought against the building owners earlier this year, so its future will be monitored closely.

West elevation detail, Delaware Building, 36 West Randolph Street, built 1872 [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

BOWEN BUILDING

66 – 70 East Randolph Street

Built 1872

Status: Orange-Rated in the CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation

This 5-story building is situated across the street from the Chicago Cultural Center, near Randolph Street and Michigan Avenue. City records indicate it was built 1881, while the CHRS shows an 1870s build date. The building is catalogued in Frank A. Randall’s book “History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago” and listed as built in 1872 by architect W.W. Boyington. It currently houses the Gallery 37 art gallery and retail store, specializing in after-school workshops and art classes for students.

PAGE BROTHERS BUILDING

177 – 191 North State Street

Built 1873 (John Mills Van Osdel, architect)

Status: Protected by Landmark Designation on January 28th, 1983

With its simplistic, unadorned look, the State Street façade of the Page Brothers Building makes this 6-story structure appear younger than it is, but the decorative Italianate bracketed cornice gives away its true age. The north elevation (far left) obscured by the Lake Street elevated rail showcases one of two Post-Fire era cast-iron façades remaining in the Loop.

Renovated west elevation, Page Brothers Building, 177 – 191 North State Street [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

The building was designed by John Mills Van Osdel, whose cast-iron façade creations once lined a half-mile of Lake Street both east and west of State Street. Downtown commercial activity, once centered on Lake Street, migrated over to State Street at the beginning of the 20th Century, and the State Street façade of the Page Brothers building was renovated and improved to fit modern tastes. It was designated a Chicago Landmark on January 28, 1983.

Original cast-iron façade on the north (Lake Street) elevation of the Page Brothers Building. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

RANDOLPH-WABASH GROUP

Built 1875 – 1878

Couch Estate Building 139 – 143 North Wabash Avenue, 1878 (John Mills Van Osdel, architect)

Peck Estate Building 133 – 137 North Wabash Avenue, 1878 (John Mills Van Osdel, architect)

Burton Estate Building 129 North Wabash Avenue, 1875

Status: Orange-Rated in CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation

Façade details of Couch Estate, Peck Estate, and Burton Estate Buildings, 129 – 143 North Wabash Avenue, built 1875 – 1878. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

The Couch Estate and Peck Estate buildings, seen below, are also Van Osdel designs, Italianate in nature with contrasting variations on the arched window bay. The rounded and flattened arch window hood designs of the Peck Estate Building are reminiscent of the Osborne & Adams Leather Company Building.

Couch Estate Building and Peck Estate Building, 133 – 143 North Wabash Avenue, built 1878. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

As noted in the 1989 Chicago Tribune article cited at the beginning of this article, landmark status was sought for this collection of buildings near the intersection of Randolph Street and Wabash Avenue, but was ultimately not obtained. In 2005, the 57-story Heritage At Millennium Park residential tower was constructed just to the east at 130 North Garland Court (another “named alley” of the Loop). The original Couch, Peck and Burton Estate buildings were lost but their historic façades were saved, and became part of the Heritage redevelopment—the upper floors conceal the parking ramp and garage for the tower (more on this contemporary practice in the “21 South Wabash Avenue” section below).

The Burton Estate Building appears very similar to the Kent Building of the Lake-Franklin Group and other vernacular Italianate commercial buildings, with red brick and the repeated masonry window hoods with a single foliated detail. The Wabash Avenue elevated rail runs adjacent to the buildings, and current ground-floor tenants include women’s clothing retailers, a fitness center, and a jeweler.

WABASH-MADISON GROUP

Built 1875 – 1877

Barker Building 18 – 20 South Wabash Avenue, 1875 (Wheelock and Thomas, architects)

Haskell Building 22 – 24 South Wabash Avenue, 1875 (Wheelock and Thomas, architects)

Atwater Building 26 – 28 South Wabash Avenue, 1877 (John Mills Van Osdel, architect)

Status: Protected by Landmark Designation on November 13, 1996

Atwater, Barker, and Haskell Buildings, 18 – 28 South Wabash Avenue, built 1875 – 1877. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

This is another collection of 4- and 5-story Post-Fire buildings on Wabash Avenue, just two blocks south of the Randolph-Wabash Group described above. The Haskell and Barker Buildings are four stories tall with a Classical Revival stone façade topped with a sheet metal cornice. The bottom floors of the Haskell Building were remodeled in 1896 by master architect Louis Sullivan, and his distinctive type of organic ornament done in cast-iron is used to surround the storefront windows.

This ornament had been covered and painted over after its 1927 occupancy by Carson Pirie Scott, and forgotten until an excellent, painstaking 2008-2009 restoration effort by current owners to renew the building’s 19th-Century appearance, as a part of the larger Sullivan Center. It is significant because it’s a precursor to Sullivan’s exquisite design at the former main store of Carson Pirie Scott at State and Madison Streets (now a Target store).

![Barker and Haskell Buildings, 18 - 22 South Wabash Avenue [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DSC_4657-1024x836.jpg)

Sullivan cast-iron ornament on the Haskell and Barker Buildings, 18 – 24 South Wabash Avenue [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

detail of Atwater Building, 26 – 28 South Wabash Avenue, built 1877. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

21 South Wabash Avenue

Built 1872 (Frederick Baumann, architect)

Status: Green Rated in CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation

The elaborate masonry facade is almost all that remains of the original building at 21 South Wabash Avenue. In 2004, the Landmarks Commission approved the demolition of some of the stretch of landmarked structures at 21 – 37 South Wabash Avenue in order to construct the postmodern 70-story Legacy At Millennium Park tower behind it to the east.

As with the buildings of the Randolph-Wabash Group, the existing façades were saved to maintain Wabash Avenue’s historic character, and were incorporated into the tower’s development. This practice can be seen as an example of a startling redevelopment trend, a kind of preservation “compromise” in today’s economy: preserving the facade of a historic building and completely replacing what’s behind it, disposing of the building’s 3 dimensional nature.

However, Holabird & Roche’s Sharp Building at 37 South Wabash was ultimately preserved and this one, along with buildings going north up to 21 South Wabash, are now occupied by the School of The Art Institute of Chicago. The architectural details seem to echo that of Van Osdel’s designs, and exhibit Italianate motifs like incised keystones and flattened arch window bays.

ADAMS STREET GROUP

Built 1872

Stone Building: 15 – 23 West Adams Street

Palmer Building: 25 – 27 West Adams Street (Charles M. Palmer, architect)

Status: Red-Rated in CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation

This remarkable group of buildings is the second largest collection of Post-Fire buildings after the Lake-Franklin Group. As with that group, a strong application of the Italianate style imitates downtown’s Pre-Fire architecture. The famous Berghoff Restaurant resides in this building group, since 1898, as seen in the below image.

The Stone Building is divided into three sections, and features a smooth, sandstone façade detailed with incised lines and rounded and flattened arch window openings. Its third story once housed a public meeting hall, and is last remaining example in the Loop of this once-common usage. The look of 15 and 19 East Adams is virtually identical in nature. Simple keystones crown most of the second-story windows, with a beautiful “bifora” double-arched window featured in the middle of the second story of 17 East Adams.

A 2006 Chicago Tribune article chronicles their history and the unsuccessful attempt to protect these buildings with landmark status—although they are clearly a significant part of Chicago’s history and its surviving Post-Fire architectural inventory.

According to this 2006 Tribune piece:

In 1991, the Chicago City Council voted against designating the Berghoff buildings. The Council sided with the restaurant’s owner, Herman Berghoff, who said that landmark status would severely reduce the value of his property by sharply restricting changes that could be made to it.

This argument can be seen time and time again in efforts to protect Chicago’s historic architecture: the economic concerns of ownership always seem to trump the urgent importance of protecting Chicago’s architectural history.

The Palmer Building, seen below, features the other surviving cast-iron façade in Chicago’s Loop. These prefabricated façades were put together on site and fastened to the building’s load-bearing masonry walls. Abstract incised designs are meant to emulate stone decoration, and the symmetric repetition of a single design across 18 paired-window bays makes a powerful and stately presentation.

One of two remaining cast-iron façades in the Loop, at the Palmer Building, 25 – 27 West Adams Street, built 1872. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

18 – 26 East Adams Street

Built 1878 or earlier

Status: Not Listed in CHRS, Not Protected by Landmark Designation

Little is known about this pair of 2-story buildings on Adams Street near Wabash Avenue. The façades of 18 – 26 East Adams Street look very similar to that of 15 – 17 West Adams Street, with the same incised lines patterns and flattened arch window bays. However, these are not protected by landmark status or even included in the Chicago Landmarks Historic Resources Survey. The windows on 26 East Adams Street (right) appear to have had keystones originally, now replaced with bricks. A number of businesses occupy the ground floors, including a nail salon and your pick of 3 different restaurants: fast food, fried fish and Persian cuisines.

CONCLUSIONS

I recognize that this was a highly ambitious project, and what I have tried to present here may be lacking in some respects. But I also felt it was an urgent and imperative undertaking, to document this extraordinary class of 140-year-old architecture now, in the fluid, ever-changing built environment of Chicago’s Loop. As we are currently experiencing with the Osborne & Adams Leather Company building (209 West Lake Street), and have witnessed in the tragic tale of the McCarthy Building, the fate of these rare Post-Fire era buildings is not secure.

The specter of economic concerns always seems to overpower our historic preservation responsibilities: a landmark designation can be granted one day, and rescinded the next. To counteract that, we need stronger, unimpeachable measures in place, with the support of our city government, to actually protect an architectural legacy of the single most important event in Chicago’s history, the Great Chicago Fire.

References and Further Reading

- “9 Buildings Seen As Landmarks” (Chicago Tribune)

- “McCarthy Building Puts Landmark Law On A Collision Course With Developers” (Chicago Tribune)

- Chicago Historic Resources Survey (City of Chicago)

- Demolition Delay Hold List 2015 (City of Chicago)

- “Developer Wants to Replace Loop Parking Garage With 33-Story Rental Tower” (Curbed Chicago)

- 209 West Lake Street demolition permit (Chicago Cityscape)

- “Loop landmark faces foreclosure” (Crain’s Chicago Business)

- Haskell, Barker, and Atwater Buildings (Harboe Architects)

- “Preservationists wary over future of Berghoff buildings” (Chicago Tribune)

- The Heritage At Millennium Park (Wikipedia)

- Legacy Tower At Millennium Park (Wikipedia)

- “Eureka! Chicago`s Total Of Cast-iron Fronts Just Doubled” (Chicago Tribune)

Very interesting and well-researched piece!

I would only add a little clarification to the “21 South Wabash Avenue” section. Namely, 37 South Wabash is a Holabird & Roche building and still exists in its entirety. It was not part of the 2004 demolition approval for the Legacy Tower. 37 South Wabash is part of the campus of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and, in fact, extends north into the 2nd and 3rd floors of 21 – 33 South Wabash with those floors used as classroom space.

Thanks so much for your input, Mike! I have revised the section to reflect your helpful comments.

Fantastic work, Gabriel!

Thanks Debbie!

Wow Gabriel! This was well worth your insomnia. The photos are amazing. What a fantastic look at Chicago architecture history!

I think it was worth it too Andi, thank you so much for your kind words!

This excellent piece of Chicago architectural history and precise research is a gift in and of itself for the clarity and promise it shares with all native Chicagoans and newly adopted inhabitants. Despite the almost perpetual stupidity and ongoing mindless greed of our politicians and would-be “urban developers” the city lives on due in part to the continual efforts of real citizens and people like Gabriel Michael. Thank you from a third generation native whose initial introduction to the magic of downtown was a birthday lunch with his (Jones school) grandmother and lifetime Harris Bank employee at Berghoff’s. Sad how even the daughter of that august institution had so little respect for what her family had built over generations. Thankfully the lightbulb finally went back on for Ms. Berghoff before her catering attempts destroyed a wonderful legacy.

Awesome job ! Makes me want to buy you a beer at Berghoffs right now !

Thank you for compiling this list! Great photos and information. THANK YOU!

Very informative and great pictures.

I moved to Chicago in the early 90’s to attend law school in the loop and enjoyed countless hours walking the area and appreciating these very buildings. I have remained a resident of the city and have had the luck to be working in the loop ever since. I am ashamed to say it never occurred to me that these magnificent historic buildings have continued to be vulnerable. Thank you for your research and excel the piece of local journalism.

Note in the pic of 18 S. Wabash the far right window on 2nd floor is smaller. At one time there was a bridge from the now demolished L station out front directly into the Carson’s store. There was a similar bridge and direct store entrance into Marshall Fields from the Randolph St. station.

As a professional guide who works with visitors from all over the world —many of whom are interested in Chicago history and architecture— let me add my thanks to Mr. Michael for his invaluable research and to those who have added to it via the comments section.

As a recently “turned on” novice to the finer points of “old” Chicago Architecture I just wanted to thank you for this introduction and list of all the Pre-fire buildings left in this city. I just discovered 175 N. Franklin this weekend myself and am now on the hunt for more. Having lived outside the city all my life (and I won’t tell you just how long that is) in a far,far south suburb I really got hooked on Chicago when I read “Devil in the White City” and now I can’t get enough. Just when I think I have seen it all I find another treasure like this. Again thank you for the information.

Also glad for preserving 14 West Randolph Street – former famous Old Heidelberg Restaurant – not named here. That builisng also have a interesting history in many ways:

(I’m living in Bergen, Norway)