Redevelopment In Sight For An Overlooked 151-Year-Old Former Factory

154 – 166 North Jefferson Street, viewing west. This building will be renovated into residences as part of the 165 North Des Plaines Street redevelopment. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

With a big transformation shaping up around the site of this unique building pre-dating the Great Chicago Fire, this article will help put a spotlight on the building’s history, and document the story of the Crane Company and and present-day conditions that have led to the changes on North Jefferson Street.

History of the Crane Company & “10 Jefferson Street”

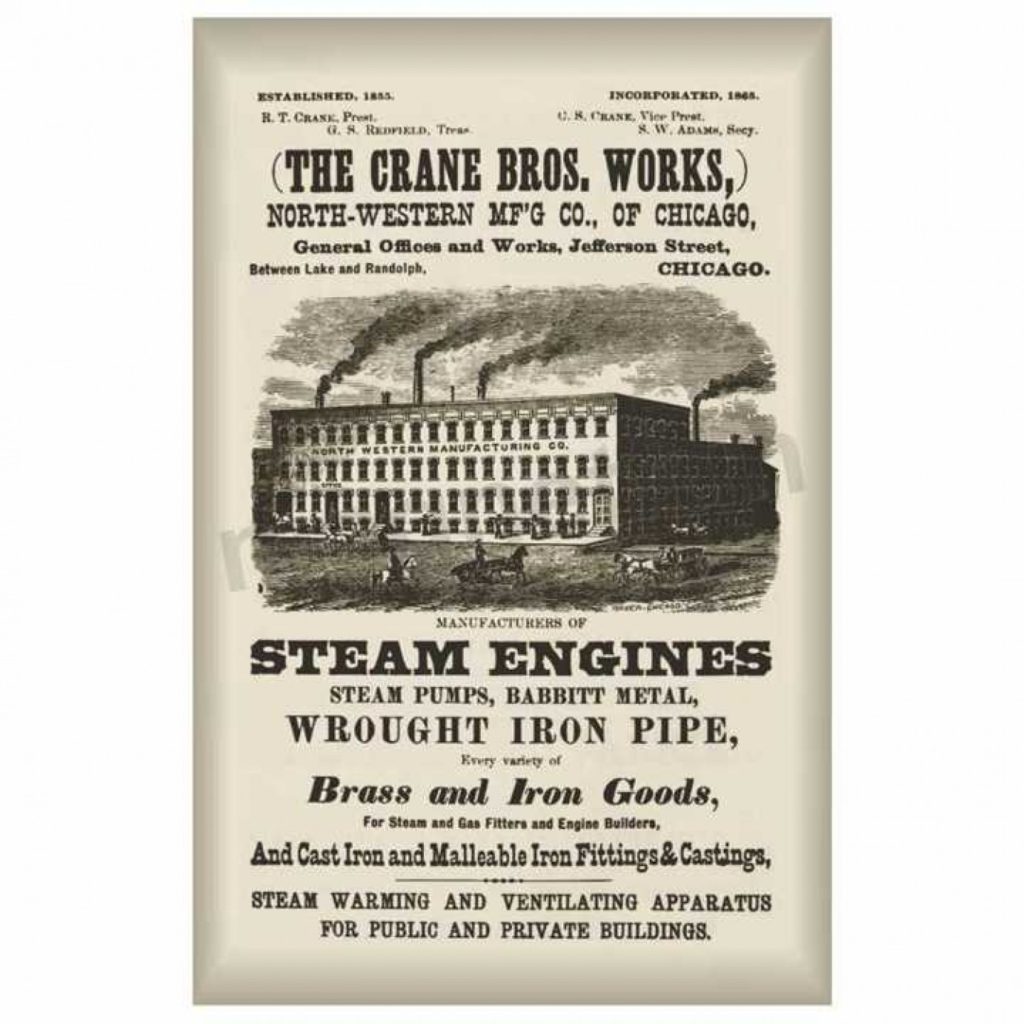

Frontispiece of The Crane Bros. Works/Northwestern Manufacturing Company catalog and price list. Depicts the west facade at 154 – 166 North Jefferson Street, and rear additions of 1870.

Richard T. (R.T.) Crane grew up in New Jersey and started his professional life as a foundry apprentice in Brooklyn. When the Panic of 1854 struck the region, he saw an opportunity to make a new start out in the developing West. Upon arriving in Chicago in 1855, he opened his first shop at the southwest corner of Canal and Fulton Streets, in a corner of his uncle’s lumberyard. Small and modest orders casting locomotive steam engine parts grew into large contracts with railcar manufacturers, as his business developed a reputation for the fine quality and craftsmanship of their work. He convinced his brother in New Jersey to join him to help manage his accelerating business in Chicago.

Evolving from basic engine parts supply, additional product lines were started by Crane, including wrought iron pipes, steam engines and pumps. With the steam heating industry just beginning to develop, Crane foresaw opportunities for rapid growth here in residential applications of his technology, not just industrial ones. He sent for experts in New York to join his business so that he could continue to produce the best quality products, and position his company among the finest in Chicago when it came to steam heating systems.

Front entrance at 154 North (formerly 10) Jefferson Street, Crane Company headquarters and foundry, built 1865 (photograph date unknown). Note the segmented brick window hoods still extant today.

In 1858, the Crane Company was awarded a $6,000 contract to furnish the Cook County Courthouse with steam heating systems. It was the largest contract of its kind in the region, and further increased orders and contracts for the well-renowned company. The start of the Civil War in 1861 also produced a boom of brass saddle fittings and wagon equipment orders for Crane. This kind of rapid growth required an expansion of their facilities and in 1864, Crane Company purchased the site at the center of this article at 154 – 166 North Jefferson Street, then 10 Jefferson Street on the city’s old, pre-standardized address system.

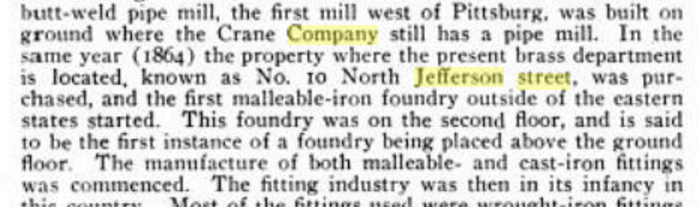

Excerpt from “Marine Engineering, Vol. 10” describing the Crane Company 1864 expansion on North Jefferson Street. The 4-story building at 154-166 North Jefferson Street was erected in 1865. Of special importance is that the Jefferson Street building was the first malleable-iron foundry in “the West”, east of Pittsburgh.

In 1865, they erected a four-story warehouse and office building with the nation’s first malleable iron foundry (also the first above ground floor) in the West. The focus of their business became steam engines and pumps, and the company incorporated as the Northwestern Manufacturing Company.

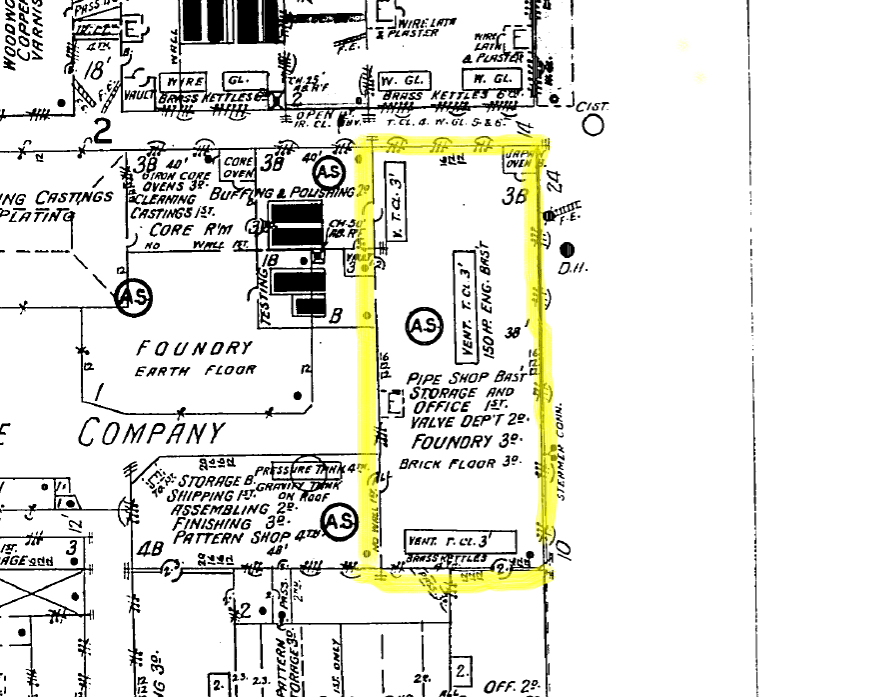

Excerpt of 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map depicting the 154 North Jefferson Street building and later additions to the south and west. Note the “10” at the lower right corner, which was the building’s pre-1909 address.

The Great Chicago Fire and the “Civic Duty” of the Crane Company

The Great Chicago Fire devastated the downtown area October 8-10, 1871, destroying its building stock and infrastructure. The Crane Company headquarters however were unscathed, situated 3 blocks west of the Chicago River, and also not affected by the terrible winds that spread the fires north across the river for miles and claimed hundreds of lives.

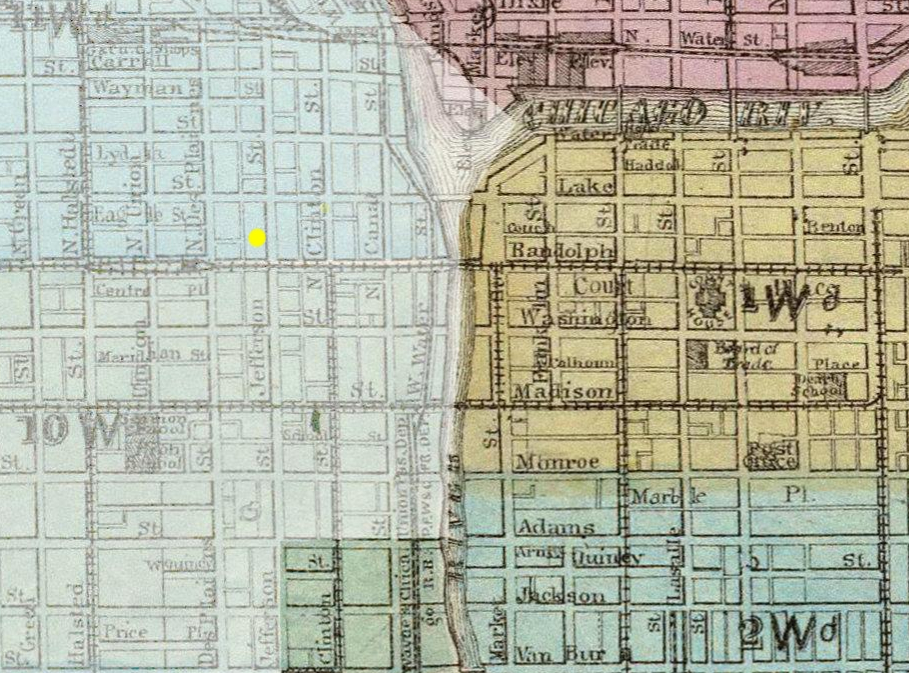

Map detail of the 1871 Great Chicago Fire coverage in the downtown area. Areas shaded in white on the west side of the Chicago River were not affected, including 154 North Jefferson Street building located at the yellow dot. (via)

In the desolate, hopeless aftermath of the Fire, R.T. Crane was emboldened with a sense of “civic duty” and “decided it was time for his company to begin to repay a debt to the city that had given an extraordinary opportunity to a penniless young man”. He provided to the city his company’s steam pump technology to pump the Chicago River at Madison Street to supply the city’s water mains.

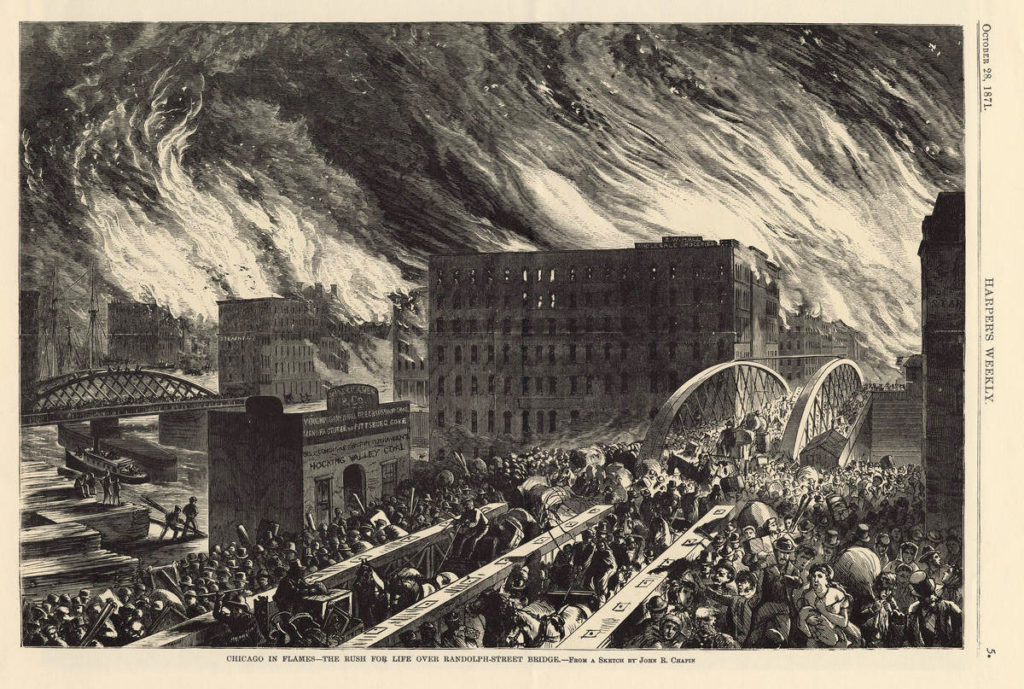

An artist’s sketch from Harper’s Weekly depicting Randolph Street at the Chicago River towards downtown during the Great Chicago Fire. The Crane Company building would have been a block away from this scene. [Wikimedia Commons]

Richard T. Crane High School, 2245 West Jackson Boulevard, built 1903. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

The Crane Company Building Today and Rapid West Loop Redevelopment

154 – 166 North Jefferson Street, viewing north. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

History shows us that the Crane Company and its founder have had an amazing, illustrious past and relationship with the City of Chicago. The Crane Company building at 154 – 166 North Jefferson Street has remained in excellent physical condition and maintained a high level of integrity to its historic architectural style, with only cosmetic alterations to replace original doorways and railings, and top-level window bays. The building is recorded in the Chicago Landmarks Historic Resources Survey (CHRS), however it is rated “Green” (the third-lowest rating in their color-coded system) which is given to “pre-1940s buildings whose exteriors have been slightly altered from their original condition”. Only ratings of “Orange” and “Red” convey any historic significance and protection upon buildings, mandating a 90-day review period when a permit is sought for their demolition.

Facade detail of 154 – 166 North Jefferson Street. Note the anchor bolts spaced evenly across the wall and layered brick corbelling on the cornice. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Another fascinating detail is the profusion of anchor bolts on the facade, forming a grid-like pattern when seen from further away—I’ve seen a lot of buildings in Chicago, and this has to be the only one I’ve seen with so many protruding bolts. This construction method is another indicator of a mid-1800s construction date, when large & heavy brick walls were fastened together horizontally by steel tie-rods with the anchor bolts (sometimes in ornamental design, like the common star shape) visible on the outside of the wall. Anchoring them to one another this way prevented lateral bowing of the heavy walls.

![Front entrance at 156 North Jefferson Street, indicating the building offices have been closed for business. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/26375519415_1c6dcc6b6d_b-998x1024.jpg)

Front entrance at 156 North Jefferson Street, indicating the building’s offices have been closed for business. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

“Xavier” residential high-rise tower development by Gerding Edlen, at 625 West Division Street. Viewing east from 1100 North Crosby Street. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

“As a firm, we have strong experience in both office and residential, and, likewise, we are always very attracted to redevelopment of historic properties as we have done in Seattle and Portland,” Edlen said. “We were really drawn to the property for those reasons. For now the property will remain as a loft office building as we assess future potential.”

Developer Gerding Edlen in “Crain’s Chicago Business”, March 25th 2015

A cluster of contemporary high-rise residential tower developments in the West Loop, east of the Kennedy Expressway. Viewing east from 700 block of West Washington Boulevard. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

The city of Chicago has enjoyed recent saves of historically-significant architecture from demolition like the unique Carl Street Studios and landmarking of West Burton Place. At the same time, we have witnessed so many lost and destroyed under similar redevelopment circumstances, such as William Van Osdel’s 209 West Lake Street building and many more. Take this particular situation: Does this building’s “slight alterations” (which arguably don’t detract from its architectural character) actually diminish its historic importance or cultural significance? Do 150 years of this building’s history become irrelevant once a doorway or window bay is changed? The lack of formal recognition of this building allows its immediate demolition once the permit is signed, another in the litany of “unknown” historic architecture lost in a city known first and foremost for its architecture.

154 – 166 North Jefferson Street, viewing southwest. The alternating window sizes, is an alteration from the original configuration. Double-door entrances with cast-iron stairwells also once sat at each end on the first story. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

References And Further Reading:

- The Surviving Post-Fire Buildings in Chicago’s Loop (Chicago Patterns)

- From A Time Before The City: the 1858 James Von Natta Farmhouse (Chicago Patterns)

- Chicago Architecture Lost in 2015 (Chicago Patterns)

- Crane: 150 Years Together (Crane Company 2005 150th Anniversary media materials)

- 154 North Jefferson Street demolition permit (Chicago Cityscape)

- West Loop building sold to Portland-based developer (Crain’s Chicago Business)

- 165 North Des Plaines Street development (ChicagoArchitecture.org)

Thank you very much for your article. But a new survey won’t prevent demolitions from occurring, even if successful in slowing them down. And the City of Chicago has enough potential landmarks to keep them busy until the end of time. Instead, preservation activists should seek a preliminary determination that the property is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. This doesn’t require owner consent and lays important groundwork should the property become threatened. Here’s where you would begin:

https://www.illinois.gov/ihpa/Preserve/Pages/Places.aspx

National Register listing doesn’t prevent demolition, but it gives the weight of the National Park Service to any future local nomination process. Even if it doesn’t go through the entire process a preliminary determination is better than nothing.

Once an active role is taken the typical preservationist realizes that they have the same problem as local government and non-profits. Namely, how can limited resources be leveraged for the greatest impact? It’s a question that should lead to more rational long-term planning for historic resources. Once you have a “preservation emergency” it’s likely the battle is already lost.

Anonymous,

Thank you for the informative response. Seeking nomination on the National Register is an avenue worth considering, and one preservationists should take more action in pursuing.

Though I don’t speak for Gabriel or his intentions in pleading for an update to the original Historic Resources Survey, I agree with his sentiment.

Your point is well taken, I understand how a new survey may not directly prevent new demolitions. But the importance of a new or revised document on the city’s historic resources goes well beyond permit applications or the court room. It can serve as a foundation for those that advocate for adaptive reuse, and help tell the story of why a place matters.

It is often too late by the time the demolition permit is granted. But there are recent cases in which a “preservation emergency” was avoided as a direct result of advocacy/outreach, after demolition was imminent:

– The James Von Natta Farmhouse: http://chicagopatterns.com/from-a-time-before-the-city-the-ca-1858-james-von-natta-farmhouse/

– The Arnold-Schwinn House: http://chicagopatterns.com/uncertain-future-vacant-gothic-mansion-built-co-founder-schwinn-bicycle-company/

– The Shrine of Christ the King: http://chicagopatterns.com/rallying-to-save-a-twice-burned-woodlawn-landmark/

In most cases reuse of historic places isn’t a result of actions by the City, but from the decision of the property owner. An accurate and updated survey would further aid efforts with property owners to seek an alternate outcome to demolition.

For people who care deeply about the built environment, it’s a right and privilege to seek outcomes which aid in the reuse and preservation of one of Chicago’s greatest assets: architecture.

Thanks for a very informative article and argument (great pics, too).

Great article that confirmed some of my past research. A friend forwarded this article to me as I am the COO from Smart Technology Services. We called this building home for Smart since 2002 and occupied the majority of the space here for most of that time. We were quite sad when the original owner, Len Flax, passed away a few years ago and the family decided to sell the building shortly afterwards. Smart and the neighborhood surrounding this building grew up together and witnessed a complete change from surface parking lots and a somewhat seedy nature, to the HQ for the CTA, multiple apartment and condo developments and old building renovations making homes for retail and restaurants. Many great memories of the brick cellars that had WWII ration canisters since the building was a bomb shelter at some point. The now filled in vaulted sidewalk that held old remnants of abandoned tools and equipment and a tunnel that used to run under Jefferson to who knows where. I don’t know what they have planned for 156, but I hope it will be renovated and continue to be a strong representation of the history of this area.

That’s a curious circular opening inside the front doorway. Any idea if this was the old forge?

The brick circle was just a decorative item done probably at the time when that the steel staircase was installed and glass entry doors installed at each floor landing.