Chicago Architecture Lost in 2015

![357 West Locust Street - St. Dominic’s Catholic Church. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/dominic-900x600.jpg)

St. Dominic’s Catholic Church was demolished in 2015. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

![First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/roumanian-5-900x600.jpg)

First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Lost Religious Structures

One of the saddest losses of 2015 was the First Roumanian Congregation, later home to Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church.

![First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/roumanian-3-900x600.jpg)

First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

The pre-fire building (1 of only 112 remaining) is facing demolition, and Preservation Chicago put it on “The Chicago Seven,” its list of the most endangered structures in the city.

Constructed at 497 (now 1352 S.) Union Street in 1869, the building’s various ownerships reflect the changing demographics of the city. Its architect was Augustus Bauer, whose firm also designed St. Patrick’s Church and the Tree Studios. A German-speaking high school, part of the neighboring German United Evangelical Zion church, was the first tenant. Beginning in 1875, a branch of the Foster School, a public school, leased the building.

![First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/roumanian-900x600.jpg)

First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

![First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/roumanian-2-900x600.jpg)

First Roumanian Congregation. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

![357 West Locust Street - St. Dominic’s Catholic Church. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/dominic2-900x674.jpg)

357 West Locust Street – St. Dominic’s Catholic Church. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Built in 1905, the church was the last remnant of “Little Sicily” just outside of downtown.

![357 West Locust Street - St. Dominic’s Catholic Church. [Gabriel X. Michael]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/dominic1-900x657.jpg)

357 West Locust Street – St. Dominic’s Catholic Church. [Gabriel X. Michael]

Around 1900, the area population shifted again, and it became the place of “first settlement” for many Sicilian and Italian immigrants, developing into “Little Sicily” as the former Central European community began moving further north and west of the city center.

![St. Dominic's interior during demolition. [Noah Vaughn]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/dominics3-900x600.jpg)

St. Dominic’s interior during demolition. [Noah Vaughn]

![3930 South Archer Avenue - St. Agnes Parish Center. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/agnes-900x589.jpg)

3930 South Archer Avenue – St. Agnes Parish Center. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

According to the Chicago Historic Resources Survey, this community center in Brighton Park was designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White.

Graham, Anderson, Probst & White was the successor firm to D.H. Burnham and Co.

![3930 South Archer Avenue - St. Agnes Parish Center. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/agnes1-900x705.jpg)

3930 South Archer Avenue – St. Agnes Parish Center. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

![St. Agnes Parish Center. [Noah Vaughn]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/agnes2-900x719.jpg)

St. Agnes Parish Center. [Noah Vaughn]

St. Agnes Parish Center, built in 1931 as a community center for the surrounding Brighton Park neighborhood, sat vacant for years before being demolished in March 2015. I managed to get some interior photos (and meet a couple of graffiti artists at work in the gymnasium) before the place was completely razed.

![St. Mary's A.M.E. Church. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/stmary-900x674.jpg)

St. Mary’s A.M.E. Church. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

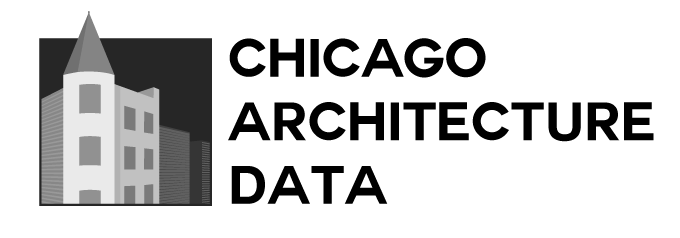

Established in 1897, St. Mary’s was the oldest African-American congregation in Washington Park.

Once surrounded by the non-extant Robert Taylor Homes, the church was surrounded by empty space.

![St. Mary's AME. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/stmary2-900x673.jpg)

St. Mary’s AME. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

In the mid-1970s St. Mary AME Church, across the street from 5266, started inviting kids from the Taylor Homes for Sunday breakfast. The kids began attending church regularly and singing in a choir. They called themselves God’s Gang, in response to the violent street gang activity in the Taylor Homes. […]

For many years the choir was the group’s only activity. It operated on a shoestring budget, with no permanent staff or funding. It traveled around the city, singing, dancing, and performing a play called The Life of Christ: Then and Now, which featured a Jesus born in the projects and a Joseph who’d fought in the gulf war.

— Neal Pollack

Though the St. Mary’s AME Church building is gone, God’s Gang continues work today.

Building announcement from June 12, 1899, Chicago Daily Tribune

![St Mary's cornerstone. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/stmary_cornerstone-900x603.jpg)

St Mary’s cornerstone. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

![Marcy Center prior to demolition. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/marcycenter-900x664.jpg)

Marcy Center prior to demolition. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Another heartbreaking loss is the Marcy Center, which was home to a Head Start center in North Lawndale. The center closed in 2013 due to lack of funding.

Labor Trail gives an account of the history of this former institution:

Part of the Marcy-Newberry Association, North Lawndale’s Marcy Center grew out of the response to the Jewish population’s move west from the Near West Side. Originally founded in 1883 by Elizabeth Smith Marcy, the group purchased a small building at 300 West Maxwell Street. In 1930, the group broke ground on the North Lawndale building. From the beginning, the Marcy Center has provided job training, youth recreation programs, daycare, and adult education. As African Americans moved into the area from other parts of the city and southern states, the Marcy Center remained committed to the community. In 1951, the center recruited Hazzard Parks of Exmore, Virginia, who had been working in New Orleans, to come to the Marcy center. Parks became the head of the Center, and a leading figure in the North Lawndale community groups and public anti-poverty programs.

Only an empty field remains where this historically significant structure once stood.

![4500 West Division Street - Salerno Cookie Co. factory. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/salerno-900x623.jpg)

4500 West Division Street – Salerno Cookie Co. factory. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Lost Bakeries

Another architectural treasure lost this year was the Art Deco-styled Salerno Cookie Company.

![4500 West Division Street - Salerno Cookie Co. factory. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/salerno1-900x673.jpg)

4500 West Division Street – Salerno Cookie Co. factory. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

An Art Deco-era factory that has long anchored a stretch of Division Street in Humboldt Park is currently being demolished. According to preservationists, the building that spans from 4422 to 4500 West Division Street was listed on the city’s 90 day demolition delay list, but was released before that period had been reached. The sprawling factory was once home to the Salerno Butter Cookie company, and similar to the old Wrigley Gum Factory and the Brach Candy Factory which have also been demolished in the last couple of years, helped make Chicago the “Candy Capital of the World.” In a joint statement, Preservation Chicago’s Ward Miller and Andrew Schneider reveal that preservationists were not made aware of the situation until it was too late.

Entrance to former Salerno Cookie Co. Photo courtesy of Debbie Mercer.

Gonnella Baking Co. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Gonnella Baking Company [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Gonnella Baking Company [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Crain’s Chicago reports that a 363-unit apartment building will occupy the site.

![Cedar Hotel. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/hotel-1-900x600.jpg)

Cedar Hotel. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Facadism: An Insult to Preservation

The circa 1928 Cedar Hotel designed by Rissman & Hirschfeld at 1112 N. State Street was preserved in some sense. Developers deconstructed the facade prior to demolition, with plans to reconstitute it in front of a new boutique hotel.

Putting a reconstructed face on a brand new building often results in an obscene juxtaposition, often worse than complete demolition.

There are alternatives to facadism. St. Ignatius College Prep is a priceless museum of architectural artifacts from long-demolished buildings.

![Wm. Ruehl's Hall, built 1894. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/hall1-900x761.jpg)

Wm. Ruehl’s Hall demolished in 2015. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Gone: Beer Brewing History

Wm. Ruehl’s Hall, a unique though structurally troubled commercial/residential building on the West Side met its end this year.

![Former Wm. Ruehl's Hall Coca-Cola signage. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ruehl-900x598.jpg)

Former Wm. Ruehl’s Hall Coca-Cola signage. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

This three-story Queen Anne-style building with Palladian windows and long-since removed corner turret, ground-floor storefront, and apartments on the upper floors, was built in 1894 and initially served as a beer hall for Mr. William Ruehl for about 15 years. Since then, it had experienced several waves of changes and repurposing, as a corner general store with Coca-Cola signage in the 1960s, and most recently as the Toolbox Lounge, a neighborhood tavern.

Throughout its lifetime, it was foreclosed upon and sold many times, and in late 2014, there was a final yet unsuccessful attempt to sell the building. In January 2015, a demolition permit for the structurally-deficient building was granted by the City of Chicago, and it was ultimately torn down and removed between February 23 – March 2.

— Gabriel X. Michael

In the 1887 book Half-Century’s Progress of the City of Chicago, the brewery received a glowing recommendation: “The beer of the Wm. Ruehl Brewing Co. is a favorite with consumers while physicians recommend it as a healthful beverage.”

Former Wm. Ruehl’s Hall. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Ruehl learned the art of stone cutting in Germany where he was born. He continued the trade when he moved to the United States, up until the founding of his brewery in 1882.

Wm. Ruehl’s Hall, more recently home to Toolbox Lounge. [Katherine Hodges]

![Standard Brewery Tied House. [Gabriel X. Michael]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/standard-900x744.jpg)

Standard Brewery Tied House. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Standard Brewery was a pre-Prohibition era brewery located in Chicago’s Tri-Taylor neighborhood at 2500 West Roosevelt Road (Roosevelt and Campbell) and was in business from 1892 until 1923. […]

At the time, this decorative building on the southwest corner served as a “tied house”, a unique retail arrangement prolific in Chicago to exclusively serve and sell beer produced by one brewery. The obvious advantage of this arrangement to a brewery was a consistent demand of its product; a tied house would not change its supplier suddenly so, while consumer choice may have suffered, the brewer had a consistent market for its beer production.

Standard Brewery detail. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Demolition of the former Standard Brewery Tied House on July 13th. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

![734 S. Sacramento. [Noah Vaughn]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/734-900x601.jpg)

734 S. Sacramento. [Noah Vaughn]

Commercial/Residential at Sacramento and Lexington

734 S. Sacramento was a mid-1890s building that housed a variety of businesses over the years, including a grocery, a pharmacy, and a dental office.

![734 S. Sacramento. [Noah Vaughn]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/comingsoon-900x443.jpg)

734 S. Sacramento. [Noah Vaughn]

I guess the 5 apartments and Seniors Youth Neighborhood Center (and Happy Sack, “Home of the Big Boy Rainbow Cone”) never panned out. Too bad.

— Noah Vaughn

![Gray buildings at 500 N. Milwaukee. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/gray-4-900x600.jpg)

Gray buildings at 500 N. Milwaukee. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

Gray Buildings at Milwaukee/Grand/Halsted

The year began with the loss of long-vacant gray buildings near the Grand Blue Line station:

After years of neglect and vacancy, it requires a leap to see the historic and architectural value of these buildings bound by busy thoroughfares on all sides. But if they retained their original ornament and fenestration and hadn’t been left to rot for so long, public sentiment regarding their loss would be different. […]

Teardown projects are frequently on opposite ends of the efficiency spectrum: high density mixed-use buildings and gaudy mansions made from inexpensive materials with multi-car garages. The former is generally admirable and the latter generally frowned upon, but it’s hard to cheer the loss of buildings more than 120 years old.

![Gray buildings during demolition. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/gray-900x600.jpg)

Gray buildings during demolition. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

![Kimbark Theater. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/kimbark-900x657.jpg)

Kimbark Theater. [Gabriel X. Michael/Chicago Patterns]

Kimbark Theater

Woodlawn’s last remaining theater was lost in 2015.

![Madison and Wabash Station. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/madisonwabash-900x595.jpg)

Madison and Wabash Station. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

According to Graham Garfield at chicago-l.org, Madison/Wabash was the last stop on the east leg of the Loop to retain its original station house.

![Madison and Wabash. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/wabash-900x600.jpg)

Madison and Wabash. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

![Madison and Wabash. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/wabash-1-900x600.jpg)

Madison and Wabash. [John Morris/Chicago Patterns]

This station also employed the city’s first direct connection between an elevated station and an adjacent building. The Louis Sullivan-designed Schlesinger & Mayer (later Carson Pirie Scott Store) was attached to the station by a now-lost Sullivan-designed covered passageway, which allowed access from the south portion of the west platform across the “crystal bridge” to the famous department store, also designed by the world renowned Sullivan.

— Preservation Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago’s Ryerson and Burnham Archives has a remarkable historic photograph of the lost bridge.

Though Sullivan’s bridge was lost long ago, a pedestrian bridge above the platform gave riders a nice vantage point of the city.

![Madison and Wabash. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]](http://chicagopatterns.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/madisonwabash2-900x596.jpg)

Madison and Wabash. [Eric Allix Rogers/Chicago Patterns]

The station will be replaced by a new Washington/Wabash station.

[Closing thoughts by the Editor]

The structures covered in this article are only a fraction of what we lost in 2015. There were many more residential teardowns of turn-of-the-century greystones, 1880s Workers Cottages, and Victorian frame houses, among other styles and types.

The rapid loss of our architectural heritage should have been slowed by the Demolition Delay Ordinance passed in 2003. It requires that Orange-rated buildings, as determined by the Historic Resources Survey, get a 90-day hold period before permits are granted.

But in the vast majority of cases, it’s only a delay and little or nothing is done to deter demolition.

For residential teardowns, there are few options. There are many buyers with more money than taste, eager to replace a well-designed or historic residential building with something garish, oversized, and poorly designed.

Options are also hard to find for commercial, institutional, and religious buildings. Contributing factors to the loss of these buildings may be deindustrialization, neglect, or decades of vacancy.

Residential conversions of these buildings (particularly religious structures) are usually the only outcomes one can hope for. The rapid inward migration toward cities isn’t doing much for large vacant buildings that are difficult to convert to residential.

For information on upcoming building demolitions, check out Chicago Cityscape’s Demolition Tracker, which tracks permits for the most recent seven days.

Chicago Patterns photographers John Morris, Gabriel X. Michael, and Eric Allix Rogers contributed to this article.

Special thanks to Noah Vaughn, Debbie Mercer, and Katherine Hodges for additional photo contributions.

Really great photos and interesting history about the buildings. Thanks!

Thanks for putting this together! Sad to lose all of these great structures but glad to know there are people who still care.

Dan

Awesome blog entry, and it pains me that Saint Dominic’s got torn down. It’s kinda miraculous that Saint Boniface hasn’t been demolished, looking at other former churches that’ve been posted here. If you ever want to(dunno if you have a Flickr group for Chicagoland architecture pics), I’d be glad to allow you the right to use my pics for a future blog entry.